New York City and Its Discontents, in 3 New Books

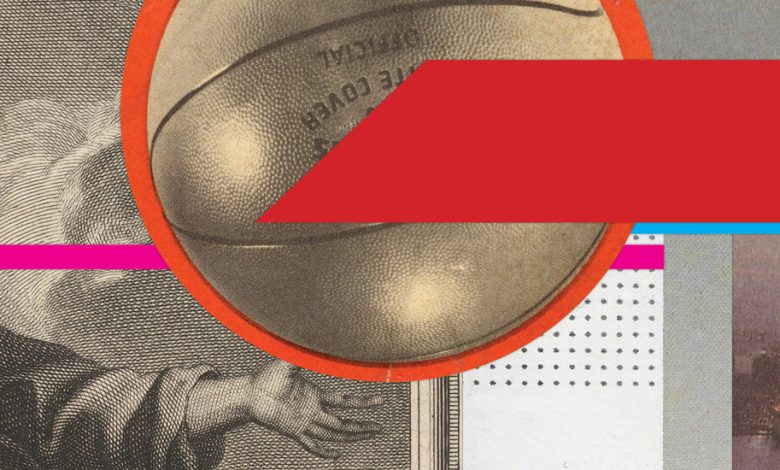

Some of the most memorable fiction about sports centers on elite athletes with a penchant for the philosophical. They’re the main players in Chad Harbach’s “The Art of Fielding” (2011) and Don DeLillo’s “End Zone” (1972), and also in Matthew Salesses’s new novel, THE SENSE OF WONDER (243 pp., Little, Brown, $28). The book focuses on the fractious relationship between two New York Knicks teammates and the larger issues of race, class and fidelity that they — and the friends and lovers in their orbit — must reckon with.

Won Lee, a Korean American point guard and one of this novel’s two narrators, has the distinction of being the N.B.A.’s only Asian American player. “New York signed me as a marketing strategy,” Won muses early in the book — but his career abruptly takes a turn for the better when the team’s star player, Paul “Powerball!” Burton, injures his back and Won emerges as a formidable figure on the court. His rise to stardom alters his relationship with the sportswriter Robert Sung, a high school teammate of Powerball!’s who had dreamed of basketball stardom before an injury ended his career. Won observes that Sung “acted as if his life was still conditional,” which anticipates the ways in which Sung’s insecurities and resentments begin to curdle into something toxic.

Much of this novel is about perception — including, but not limited to, the racist microaggressions Won experiences from fans and team staff members alike. The novel’s second narrator, Carrie Kang, brings those questions of perception into sharp focus. She and Won are in a relationship for much of the novel, but it’s her job as a producer of K-dramas, one of which is about a basketball player, that plays out as a kind of remixed version of the conflicts in Won’s and Carrie’s lives.

The dual narration allows Salesses to subtly illustrate the ways his characters’ lives do and do not overlap. From Carrie’s chapters, the reader learns that her sister is struggling with a cancer diagnosis — a subplot that doesn’t come up at all in Won’s chapters. It reflects their differences — and what each of them has going on outside of their respective careers. And while there’s plenty of rumination on basketball in an age of celebrity, it’s far from the only concern in this ambitious, expansive work.

Dan Kois’s VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES (317 pp., Harper, $27.99) opens in 1991, not long after a young woman named Em has moved to New York City. Em is short for Emily, though she adopts the diminutive only after she befriends another Emily at the restaurant Veselka. The latter notes that “it would be pretty confusing that we were both named Emily” if they were characters in a story — one of a few winking, metafictional moments scattered throughout the book.

Emily’s artistic interests are in the theater, while Em has designs on a publishing job. Em has a particular fondness for the Random House imprint Vintage Contemporaries, though when the novel jumps ahead in time to 2005, its title takes on another aspect, addressing the ways that friendship of a certain vintage can deepen — or atrophy — over the years. But while their relationship and its more fraught aspects over the years are a big part of the novel — and could likely have sustained a book on its own — there’s more to the story.

“Vintage Contemporaries” has an unusual choice of epigraph: the marketing copy from the front cover of Laurie Colwin’s novel “Happy All the Time,” which reads: “Life never worked out so well! Love never had it so good!” Colwin, who died in 1992, doesn’t appear in Kois’s pages, but a writer with some similarities to her does — Lucy Deming, a friend of Em’s mother and a published author who is looking for a home for her next book. Em’s first full-time job in New York is at a literary agency, so the bond that forms between her and Deming winds up being both personal and professional.

The weaving plotlines ultimately amount to a story about a woman learning what kind of art matters to her, whether it’s the more cutting-edge writing of the likes of Mary Gaitskill and Kathy Acker, both of whom are mentioned here, or the work of Lucy, who has no interest in being edgy. (Emily, who says early on that “as a rule, I don’t read novels from after 1947,” is in a wholly different aesthetic camp.) Not every subplot clicks into place perfectly: Em’s dealing with structural inequality in the publishing industry doesn’t have the same force as the clashes with mortality, addiction and the Giuliani administration that arise elsewhere. But the cumulative effect of these disparate threads is considerable; it’s a novel that is both an argument about art and a compelling example of it.

These are some things you might learn about the Met Museum in New York upon reading Patrick Bringley’s ALL THE BEAUTY IN THE WORLD: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me (228 pp., Simon & Schuster, $27.99), an account of the 10 years he spent working there: The Met has one of the largest collection of baseball cards outside of the Baseball Hall of Fame; many of its security guards are immigrants from Guyana, Albania and Russia; and guards receive an annual allowance to cover the cost of socks. Bringley’s memoir abounds with small details like these, accrued over his own time working as a museum guard, but it also has grander subjects to address — namely, solitude, the staying power of art, and grief.

Bringley describes objects from around the world, covering thousands of years of history. But he returns again and again to images of Christ — not out of religious devotion necessarily, but because of the parallels between one man who died far too young and Bringley’s older brother, who died of cancer when he was 26. It was in the wake of that death that Bringley left his job at The New Yorker and sought something else, a decision that brought him to a storied museum on the edge of Central Park.

“I am reminded again how different are the experiences of reading books and looking at art,” Bringley writes. It’s an acknowledgment of the challenges of trying to convey both the expanse of a museum and the tribulations of a family into a concise work of nonfiction. In the end, “All the Beauty in the World” is an empathic chronicle of one museum, the works collected there and the people who keep it running — all recounted by an especially patient observer.

Tobias Carroll is the author of four books, most recently the novel “Ex-Members.”