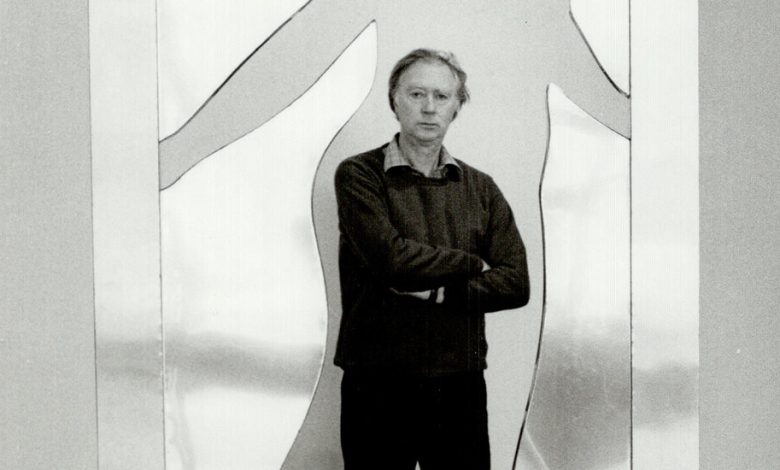

Michael Snow, Prolific and Playful Artistic Polymath, Is Dead at 94

Michael Snow, a Canadian painter, jazz pianist, photographer, sculptor and filmmaker best known for “Wavelength” — a humble, relentless, more or less continuous zoom shot that traverses a Lower Manhattan loft into a photograph pasted on its far wall — died on Thursday in Toronto. He was 94.

His wife, Peggy Gale, said the cause was pneumonia.

“Wavelength” (1967), hailed by the critic Manny Farber in Artforum magazine in 1969 as “a pure, tough 45 minutes that may become the ‘Birth of a Nation’ in Underground film,” provided 20th-century cinema with a visceral metaphor for itself as temporal projection. If it also saddled Mr. Snow with the weight of an unrepeatable masterpiece, it was a burden he bore lightly.

Mr. Snow was a prolific and playful artist, as well as a polymath of extraordinary versatility. “I am not a professional,” he declared in a statement written for a group show catalog in 1967. “My paintings are done by a filmmaker, sculpture by a musician, films by a painter, music by a filmmaker, paintings by a sculptor, sculpture by a filmmaker, films by a musician, music by a sculptor.” And, he added, “Sometimes they all work together.”

Whatever his medium, he seemed to be constantly rethinking its parameters. “A Casing Shelved” (1970) is a movie fashioned from a single projected 35-millimeter photographic slide showinga bookcase in his studio and a 45-minute tape recording of Mr. Snow describing the case’s contents.

In the 16-millimeter film “So Is This” (1982), which consists entirely of text, each shot shows a single word as tightly framed white letters against a black background. Another film, “Seated Figures” (1988), is a 40-minute consideration of landscape from the perspective of an exhaust pipe; to make that film, Mr. Snow attached the camera to the carriage of a moving vehicle.

He began his film career with animation and capped it with the digitally produced feature “*Corpus Callosum” (2001), a cartoonish succession of wacky sight gags, outlandish color schemes and corny visual puns rendering space as malleable as taffy. Because he was waiting for technology to catch up with his vision, the film took 20 years to realize.

Mr. Snow’s work was often based on the paradox of two-dimensional representation and sometimes demanded a physical or psychological shift in the viewer’s position. “Crouch, Leap, Land” (1970) requires the viewer to scrunch down beneath three suspended Perspex plates.

“Mr. Snow’s approach to photography is both heady and physical, a rare combination,” Karen Rosenberg wrote in The New York Times in a 2014 review of a retrospective devoted to his photography at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “The show makes you wonder, though, why Mr. Snow’s photography isn’t as well known as his films.”

The reason may be that his best-known film was a true cause célèbre — the most outrageous American avant-garde film after Jack Smith’s quite different “Flaming Creatures” (1963). Laurence Kardish, a former film curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, said a screening of “Wavelength” in March 1969 was disrupted by “shouts and counter shouts and walkouts.” Many attendees of MoMA’s screening, part of its often experimental Cineprobe series, were “lost,” Mr. Kardish recalled in an interview for this obituary in 2016, although he said he believed Mr. Snow “enjoyed the brouhaha.”

In an interview in 1971 with the Canadian film magazine Take Out, Mr. Snow recalled that the first screenings of an earlier film, “New York Eye and Ear Control” (1964) — which combined a cacophonous free-jazz soundtrack with a classically constructed non-narrative montage — caused disturbances both in New York and in Toronto, where “somebody wrote a review with a headline saying ‘300 Flee Far Out Film.’”

Take One quoted that headline on its cover. Inside, the filmmaker and writer Jonas Mekas described a recent screening of “Wavelength” at the Anthology Film Archives in New York:

“There were fist fights in the auditorium and at least two members of the audience were seen with handkerchiefs on their faces, all bloody, and someone stood up in the auditorium and shouted, loud and angry: ‘I know what art is! I studied art in Italy! This is a fraud! I’ll get Mayor Lindsay to close this place.’”

Mr. Snow’s sequel to “Wavelength” was a film titled with a double arrow in which, for 52 minutes, the camera — positioned in a nondescript classroom — pans back and forth and sometimes tilts up and down to create what might be called a perpetual motion picture.

Michael James Aleck Snow was born in Toronto on Dec. 10, 1928, the son of Gerald Bradley Snow, a civil engineer, and Marie-Antoinette Françoise Carmen (Lévesque) Snow. The family was distinguished. One of Mr. Snow’s paternal great-grandfathers, James Beaty, had been mayor of Toronto and a member of Canada’s Parliament in the late 19th century; more recently, his maternal grandfather, Elzear Lévesque, had served as the mayor of Chicoutimi, Quebec, about 125 miles north of Quebec City.

Mr. Snow attended Upper Canada College and the Ontario College of Art, from which he graduated in 1952. He made his first film, the animated short “A to Z,” in 1956 (an excerpt from it was included in “*Corpus Callosum”) and had his first solo exhibition soon after. In 1961, he introduced a stylized, curvaceous silhouette, which he called the Walking Woman, that would be his trademark for much of the 1960s.

The silhouette was featured in paintings, sculptures and photographs, as well as in “New York Eye and Ear Control.” — a movie notable for its improvised soundtrack by the saxophonist Albert Ayler, the trumpeter Don Cherry, the bassist Gary Peacock and the drummer Sunny Murray. (Mr. Snow never played formally with these musicians, but he did have a combo, continuously called CCMC despite its shifting personnel, with whom he cut several albums and regularly performed in Toronto.)

The Walking Woman project continued after Mr. Snow and his wife, the artist Joyce Wieland, moved to New York City in 1963 and became part of a group of avant-garde artists that included the composer Steve Reich, the sculptor Richard Serra, the playwright Richard Foreman and the filmmakers Hollis Frampton and Ken Jacobs, as well as the critic Annette Michelson and a number of jazz musicians, among them the pianist Cecil Taylor.

Increasingly concerned with Canadian subject matter, Mr. Snow and Ms. Wieland returned to Toronto in the early 1970s. They divorced in 1990, and Ms. Wieland died in 1998. Mr. Snow married Ms. Gale, a curator and writer, in 1990. In addition to her, Mr. Snow, who lived in Toronto, is survived by their son, Alexander Snow, and a sister, Denyse Rynard.

Mr. Snow’s first Canadian feature was “La Région Centrale” (1971), which used a computer-programmed, motorized tripod that could rotate the camera 360 degrees in any direction to create a vertiginous three-hour landscape study; back in Canada, he continued to work in a variety of media and revived his music career with the CCMC ensemble.

In 1979, Mr. Snow was commissioned to create an installation for the atrium of the Eaton Center, a new multilevel mall in downtown Toronto. The piece, “Flight Stop,” consisted of 60 life-size Canada geese fashioned from fiberglass and suspended from the top of the atrium, frozen in flight. When the Eaton Center festooned the birds with ribbons for the Christmas season, Mr. Snow enjoined it to remove the decorations on the grounds that his intentions had been compromised. The Ontario High Court of Justice affirmed his rights, and the Copyright Act of Canada was amended to protect the integrity of an artist’s work.

“Flight Stop” became something of a municipal landmark. So did Mr. Snow himself, who went on to create more public artworks in Toronto. In 1994, a consortium of Toronto arts institutions celebrated his work with multiple gallery exhibitions and a complete film retrospective, as well as concerts, symposiums and the publication of four books, each devoted to a particular aspect of his oeuvre.

Nothing even remotely comparable was ever attempted in New York, his temporary adopted hometown, although Mr. Snow’s impact on New York’s avant-garde was considerable.

“One of little more than a dozen living inventors of film art is Michael Snow,” Mr. Frampton, his fellow filmmaker, wrote in 1971. “His work has already modified our perception of past film. Seen or unseen, it will affect the making and understanding of film in the future.

“This is an astonishing situation. It is like knowing the name and address of the man who carved the Sphinx.”

Maia Coleman contributed reporting.