Killing of Qaeda Leader Crystallizes Debate Over Biden’s Afghanistan Strategy

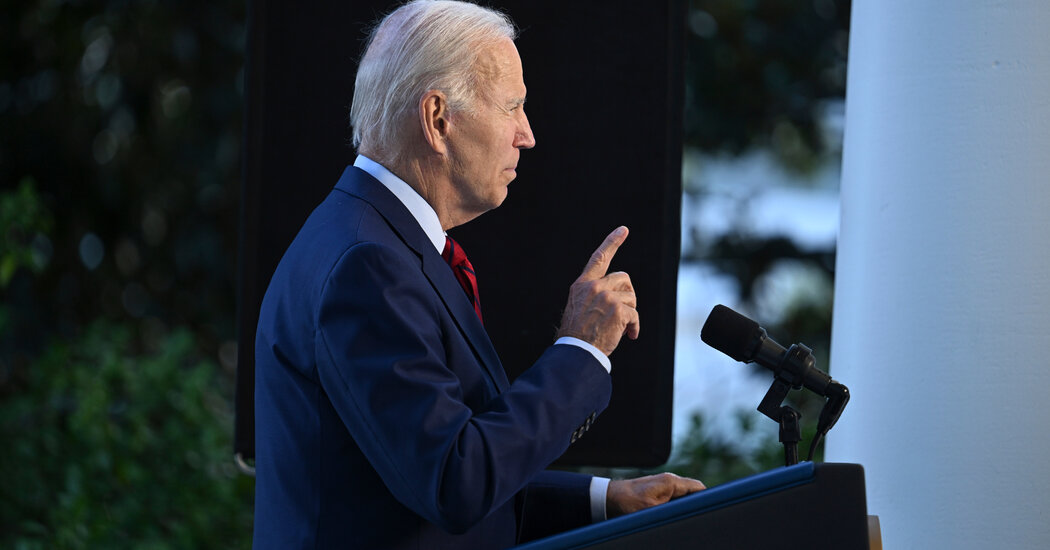

WASHINGTON — The sunrise missile strike that shredded the leader of Al Qaeda on the balcony of a house in Kabul finally validated President Biden’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan. Or perhaps the strike discredited it. Or maybe some combination of both.

The coming anniversary of the chaotic American withdrawal from Afghanistan was already sure to instigate a round of arguments about its wisdom, but the killing of Ayman al-Zawahri by a C.I.A. drone hovering over the Afghan capital has crystallized the debate in a visceral way.

To Mr. Biden and his allies, the precision operation that took out one of the patrons of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks without civilian deaths demonstrated that war can be waged against terrorists without large deployments of American troops on the ground. To his critics, though, the stunning realization that al-Zawahri had returned to Kabul evidently under the protection of the Taliban made clear that Afghanistan has again become a haven for America’s enemies.

“The successful U.S. strike vindicates those who’ve argued for an over-the-horizon counterterrorism strategy in Afghanistan,” Kate Bateman, who helped write reports for the American government on corruption, drugs, gender inequality and other issues in Afghanistan, said in a discussion hosted by the U.S. Institute of Peace. “But Zawahri finding harbor in Kabul may also point to a graver threat than was assumed.”

The dual conclusions emerging from the strike complicated an otherwise heady moment for a president who just authorized the operation that took out one of the most wanted men in the world. Hunting down and killing al-Zawahri may not have resonated with the public in the same way the raid that dispatched Osama bin Laden did in 2011, but it was nonetheless seen across the board as a victory for the United States.

The implications of that victory, however, were still being sorted out the day after Mr. Biden’s nighttime address to the nation announcing the drone strike from over the weekend. The president now confronts the question of what, if anything, he will do in response to the revelation that the Taliban were once again sheltering the leader of a group dedicated to killing Americans.

The peace agreement that led to last year’s troop withdrawal, negotiated by President Donald J. Trump before he left office and then carried out by Mr. Biden, specified that the Taliban would not allow Afghanistan to become a launching pad for future Al Qaeda violence against the United States as it was before the Sept. 11 attacks.

While the Biden administration called al-Zawahri’s presence a clear violation of that deal, known as the Doha Agreement for the capital of Qatar where it was sealed, some analysts said the Taliban could maintain that it was not out of compliance because sheltering the fugitive head of Al Qaeda was not the same as serving as a staging ground for new attacks.

The White House did not see it that way. “The Taliban have a choice,” John F. Kirby, the strategic communications coordinator for the National Security Council, told reporters on Tuesday. “They can comply with their agreement” to bar terrorists from their territory “or they can choose to keep going down a different path. If they go down a different path, it’s going to lead to consequences.”

But neither Mr. Kirby nor other officials would specify what kind of consequences Mr. Biden had in mind. There is no appetite in the White House, or for that matter most of Washington, for a return of significant military force to Afghanistan. And the Taliban leadership that swept into power in the wake of last year’s American withdrawal has successfully defied international pressure as it has reimposed a repressive regime, including a renewed crackdown on the rights of women and girls.

“We’re back to where we were before 9/11 and unfortunately that means the Taliban and Al Qaeda are back together,” said Bruce Riedel of the Brookings Institution, an adviser to multiple presidents on the Middle East and South Asia who conducted a review of Afghanistan policy for President Barack Obama when he came into office. “Twenty years of effort were wasted.”

Al-Zawahri returned to Afghanistan earlier this year, according to American intelligence reports, moving with his family into a house in one of the most exclusive enclaves of Kabul, where American and other foreign diplomats lived not too long ago only to surrender the neighborhood to Taliban figures. “He must have felt very safe, 100 percent confident that nothing could harm him,” Mr. Riedel said.

Indeed, the Taliban clearly knew al-Zawahri was there and safeguarded him. He was living in a house owned by a top aide to Sirajuddin Haqqani, the Taliban interior minister and part of the Haqqani terrorist network with close ties to Al Qaeda, according to two people with knowledge about the residence. After the strike, members of the Haqqani network tried to conceal that al-Zawahri had been at the house and restrict access to the site, senior American officials said.

Mr. Biden justified his decision to pull out last year on the grounds that Al Qaeda was no longer there. “What interest do we have in Afghanistan at this point, with Al Qaeda gone?” he said at the time. “We went to Afghanistan for the express purpose of getting rid of Al Qaeda in Afghanistan as well as getting Osama bin Laden. And we did.”

Mr. Kirby argued on Tuesday that the president meant that Al Qaeda was no longer a significant force in Afghanistan by that point, noting that government assessments at the time concluded the group’s presence was “small and not incredibly powerful.” Mr. Kirby added, “We would still assess that to be the case.”

As a result, he and other officials said, the strike on al-Zawahri showed that even without the Taliban living up to its commitments, the United States retained the ability to take out threats in Afghanistan by employing military forces based elsewhere in the region, or over the horizon, as the strategy is called.

“It has proven the president right when he said one year ago that we did not need to keep thousands of American troops in Afghanistan fighting and dying in a 20-year war, to be able to hold terrorists at risk and to defeat threats to the United States,” Jake Sullivan, Mr. Biden’s national security adviser, said on ABC’s “Good Morning America.”

Still, some counterterrorism experts expressed caution. “The strike proves that over-the-horizon” counterterrorism strategy “can work — emphasis on ‘can’ — but not that it will generally,” said Laurel Miller, a former acting special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan under Mr. Obama.

“Zawahri was a special case, for which all the stops would be pulled out in terms of resources and level of effort,” added Ms. Miller, who is now at the International Crisis Group. “This operation does not automatically erase the assessment that” operating from outside the country “has significant limitations.”

Daniel Byman, a terrorism expert at Georgetown University who served on the staff of the bipartisan commission that investigated the Sept. 11 attacks, said the al-Zawahri strike proved that the United States could still wage war without troops on the ground and that without troops on the ground Afghanistan would become a sanctuary again for Al Qaeda.

“They’re both right,” he said of allies and critics of the president.

But what might be more concerning, he added, was that the flashy success of knocking off a marquee figure like al-Zawahri only goes so far in dismantling terror networks.

“From what has been reported, it does show impressive operational capacity,” he said. “However, much of the U.S. success against Al Qaeda and ISIS came from grinding decapitation campaigns that went after trainers, recruiters, planners, and other lieutenants. Doing such a sustained campaign in Afghanistan seems quite difficult.”

At the same time, Mr. Byman said, whoever succeeds al-Zawahri will presumably be more cautious, limiting communications and meetings, making it harder to actually lead a global organization. “So even being able to threaten the very top,” he said, “does have some value.”