Cold War Nuclear Bunker Lures Tourists Worried About New Threats

OTTAWA — Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine last year, Christine McGuire’s museum began receiving inquiries unlike anything she’d previously encountered during her career.

“We had people asking us if we still functioned as a fallout shelter,” said Ms. McGuire, the executive director of Diefenbunker: Canada’s Cold War Museum. “That fear is still very real for people. It seems to have come back into the public psyche.”

The Diefenbunker still has most of the form and features of the nuclear fallout shelter it once was for Canadian government and military V.I.P.s. But the underground complex, decommissioned in 1994, has shifted from being a functioning military asset to being a potent symbol of a return to an age when the world’s destruction again seems a real possibility with a nuclear-armed Russia raising the specter of using the weapons.

The Diefenbunker history is not just of global tension but also of Canada’s parsimonious approach to civil defense, optimistic thinking about the apocalypse and Canadians’ antipathy toward anything they perceive as a special deal for their political leaders. Now, the privately run museum is one of the few places in the world where visitors can tour a former Cold War bunker built to house a government under nuclear attack.

These factors have made the four-story-deep, 100,000-square-foot warren of about 350 rooms into an unexpectedly popular tourist attraction despite its off-the-beaten-path location, in the village of Carp within the city limits of Ottawa, Canada’s capital.

Robert Bothwell, a professor of history at the University of Toronto, was on the board of an Ontario cultural organization during the 1990s when a group of volunteers proposed turning the bunker into a museum. At that time, he said, several other volunteer-based museums had failed to attract visitors even with ample funding.

“So I thought: ‘Diefenbunker? Give me a break,’” he said. “But I was totally wrong.”

Since its construction began in 1959, the bunker has carried a variety of official names: Emergency Army Signals Establishment, Central Emergency Government Headquarters and Canadian Forces Station Carp. But it came to be known as the Diefenbunker after John Diefenbaker, the prime minister who commissioned it, more as a form of mockery than in his honor.

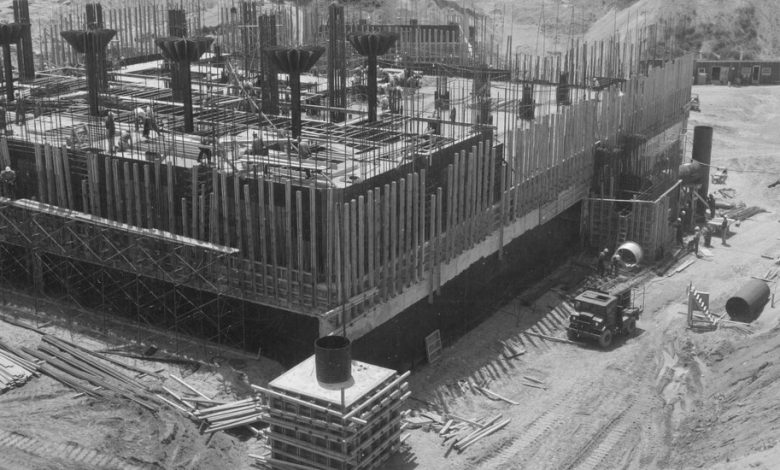

For almost two years, during its construction, the bunker and 10 other much smaller bunkers across the country were disguised as military communications centers, which, in fact, was part of their role.

But The Toronto Telegram newspaper exposed the Diefenbunker’s true nature in 1961 with a detailed aerial photograph of its construction site. The photograph showed that dozens of toilets were to be installed, a sign that the complex would be more than a small radio base. Above the photograph, the headline read: “78 BATHROOMS — and the Army still won’t admit that … THIS IS THE DIEFENBUNKER.”

Unlike the United States, Canada did not establish an extensive network of stocked fallout shelters to protect civilians, said Andrew Burtch, a historian at the Canadian War Museum and the author of a book about the country’s limited civil defense system.

Part of it was simply cost, he said. But he said that the military also assumed that the Soviets had reserved their then-limited number of warheads for the United States and would not “waste” them on Canadian targets. In that scenario, planners assumed that radiation from Soviet bombers shot down over Canada would be the main threat. That led, Dr. Burtch said, to a civil defense system in which, “for the most part, the public was on its own.”

Mr. Diefenbaker acknowledged the bunker’s purpose after the aerial photograph appeared and vowed that he would never visit it and would stay home with his wife if the bombers and missiles came. But outrage over the exclusive bunker — reserved for 565 people, including the prime minister and his 12 most senior cabinet ministers — persisted. Compounding the outcry, the government refused to disclose the cost of the bunker, estimated at 22 million Canadian dollars in 1958 money, or about 220 million today.

From the outside, the Diefenbunker looks like a grassy hillside with a few vents poking up from behind the ground, along with a handful of antennas, one quite tall. The entrance, added during the 1980s, is via a metal building with a roll-up garage door that opens to the blast tunnel, an area designed to absorb energy from a bomb dropped on downtown Ottawa. Stretching for 387 feet, the blast tunnel connects to a to a set of doors, weighing one and four tons each, and then next is a decontamination area that opens to the rest of the bunker.

Much of the interior of the utilitarian and brightly lit space is a restoration of the original, which was stripped after the complex was decommissioned and replaced with similar or identical items from smaller bunkers or military bases.

The prime minister’s office and suite is spartan, its only touch of luxury being a turquoise-colored washroom sink.

The war cabinet room has an overhead projector and four television sets. A military briefing room immediately next door has a projector that tracked planes.

The bunker is surrounded by thick layers of gravel on all sides to help mitigate the shock of any nearby nuclear explosions. Its plumbing fixtures are mounted on thick slabs of rubber and connected with hoses rather than pipes for the same reason.

The most secure and best protected area of the bunker was a vault behind a door so immense it requires a second, smaller door to be opened first to equalize the air pressure. It was intended as a place for Canada’s central bank, the Bank of Canada, to place gold should an attack appear imminent. There’s no record that the bank ever delivered gold there, a Bank of Canada spokesman said, and the vault became a gym in the 1970s.

A small armory was raided in 1984 by a corporal stationed in the bunker. He stole a large number of weapons, including two submachine guns, and 400 rounds of ammunition before driving to Quebec City where he shot and killed three people and injured 13 others at the province’s legislative assembly.

The complex was designed to store enough food and generator fuel to support occupants for 30 days after a nuclear attack, under the assumption that by then radiation levels above ground would be low enough for everyone to emerge.

But the need never arose, and the bunker remained scorned. Ultimately, the only prime minister to tour it was Pierre Elliott Trudeau, the father of Justin Trudeau, the current prime minister, who flew in on a military helicopter in 1976. After the trip, his government cut its budget.

Visitors stream here now from across Canada and abroad to experience for themselves this window into the Cold War past — and perhaps for a sense of the security that many crave today.

It’s also a rare opportunity to step inside a bunker built to withstand a nuclear Armageddon.

While bunkers from various wars are dotted around the world and open to visitors, major Cold War ones are much less common. A decommissioned bunker under the Greenbrier Resort in West Virginia — intended to hold all of the members of Congress — offers tours, but bans phones and cameras.

Gilles Courtemanche, a volunteer tour guide at the Diefenbunker, was a soldier stationed there in 1964, when he was 20. He worked there for two years as a signalman, setting up and maintaining communications and computer infrastructure. He was one of the 540 people, civilians and military members, who operated the bunker on three shifts before it was decommissioned.

Things have come full circle for him and for Canada. The Cold War of his youth has mutated to new kinds of threats, he said.

“It’s an important thing that we have here,” Mr. Courtemanche said, referring to the museum’s ability to remind visitors of threats past and present. “Now, China is starting to flex their muscles, and the Russians? Well, I don’t understand what they are doing at all. To me, it’s insanity.”