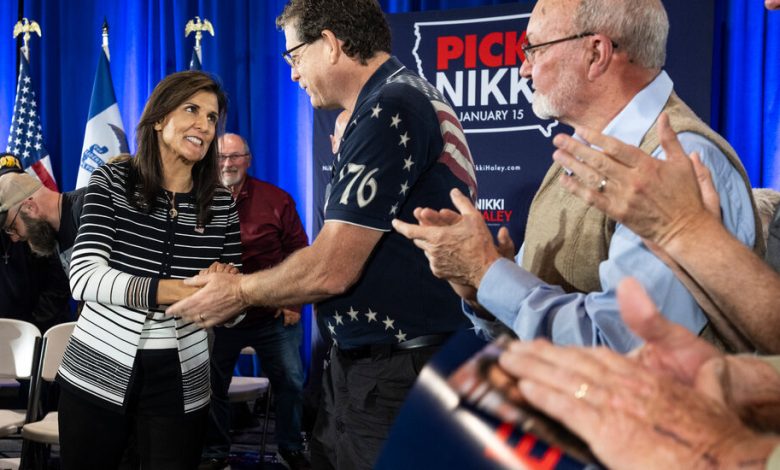

To Beat Trump, Nikki Haley Is Trying to Speak to All Sides of a Fractured G.O.P.

To beat former President Donald J. Trump in the coming months, Nikki Haley, his former ambassador to the United Nations, must stitch together a coalition of Republicans: Mr. Trump’s most faithful supporters, voters who like his policies but who have grown weary of him personally, and the smaller but still vocal contingent who abhor him entirely.

It’s a challenge that will test what political strategists and those who have observed Ms. Haley’s ascent from her first underdog win in South Carolina have said is among her greatest skills as a candidate: an ability to calibrate her message to the moment.

Since announcing her bid in February, she has campaigned much like an old guard Republican: hawkish on foreign policy, supportive of legal immigration reform and staunchly in favor of the international alliances that Mr. Trump questioned during his administration. She has also sounded a lot like the former president, whose “America First” rhetoric she echoed while serving as one of his diplomats, with aggressive calls to send the U.S. military into Mexico and remarks about the need to rid schools and the military of perceived left-wing influences on hot-button cultural issues like race and transgender rights.

Other than how she has navigated Mr. Trump himself, perhaps no issue best exemplifies Ms. Haley’s approach than abortion. She backed harsh restrictions on the procedure as governor of South Carolina and has called herself “unapologetically pro-life” on the trail, but she has struck a flexible tone as her party has flailed in countering the electoral backlash the conservative majority on the Supreme Court triggered when it overturned Roe v. Wade. Her appeals for “consensus” have been among the most common reasons cited for her upward climb in the polls in the early voting states of Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina.

Ryan Williams, a Republican strategist and a former aide to Mitt Romney who has known Ms. Haley since she was a state lawmaker first running for governor, said she “has always been a pragmatic conservative.” “She is comfortable in her own skin, and she is going to win or lose based on her own values and beliefs,” he said. Still, the difficulty for her, as for all the candidates attempting to emerge as a Trump alternative, is that “what a conservative is has been redefined by Trump himself,” he said.

Mr. Trump’s lead over the field is dominant nationally and in every early state polled, and it remains uncertain that Ms. Haley could peel away enough of his faithful, no matter her approach, to come out on top. And what has so far propelled her could also become a liability, should she alienate one or more faction. Her rivals, including Mr. Trump and Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, have sought to portray her as insufficiently conservative and as someone who panders to Democrats. Jaime Harrison, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, labeled her a “snake oil salesman” who “will say whatever she needs to say to get power.”

Her campaign officials and surrogates argue her politics have stayed the same, with the country and the world changing around her. “Nikki has always been a tough, anti-establishment conservative,” said Olivia Perez-Cubas, a spokeswoman for Ms. Haley.

Ms. Haley’s attempt to thread the needle on abortion is already being tested, as she has faced skepticism from Iowa’s evangelical community, a critical voting bloc. Addressing a conservative Christian audience in Iowa, Ms. Haley said she would have signed a ban on abortion after six weeks of pregnancy as governor.

Democrats seized on Ms. Haley’s remarks as proof that, despite her tone, she is no moderate on the issue. The influential evangelical leader Bob Vander Plaats, who previously indicated that clear-cut abortion opposition would be the driving factor for his support, went on to endorse Mr. DeSantis. But just days earlier, Ms. Haley had received a seemingly impromptu endorsement from Marlys Popma, the former head of the state Republican Party and one of Iowa’s most prominent anti-abortion activists — who indicated she was comfortable with Ms. Haley’s stance.

Here are four other issues on which Ms. Haley has shifted, evolved or otherwise tempered her positions.

Immigration and refugees

Ms. Haley first rose in politics on the deep red wave of the Tea Party — and its anti-immigrant sentiment. As governor, she signed some of the harshest immigration laws in the country in 2011, requiring law enforcement officers to ask certain people’s immigration status and businesses to verify that their workers were in the country legally.

But Ms. Haley, the daughter of Indian immigrants, largely refrained from using dehumanizing language against immigrants and stuck to the consistent message that immigration was critical to the nation, as long as it was done legally. Still, two pivotal events prompted her to take a sharp turn on the issue: the deadly terror attack in Paris in 2015, and the rise of Mr. Trump.

After the attack, Ms. Haley, who was then governor, went from supporting the efforts of faith groups to resettle refugees in South Carolina to aggressively fighting the Obama administration on the admission of Syrians fleeing violence, citing concerns over the vetting process.

Before Mr. Trump’s election in 2016, she called his proposal to bar Muslims from traveling to the United States “absolutely un-American.” As Mr. Trump’s U.N. ambassador, she defended his order to temporarily block all refugees and people from six Muslim-majority countries from entering the U. S., as well as his decision to cut American funding to Palestinian refugees.

On the trail, she has expressed support for expediting legal immigration avenues, for aiding escape from persecution and for improving the ways people can migrate, calling for a system based on merit and business needs, rather than quotas. But with a higher and more consistent frequency, she echoes Mr. Trump. She has promised to build a wall, send immigrants back and reinstitute some of Mr. Trump’s harshest immigration and asylum policies.

Tough talk on China

Ms. Haley seizes every opportunity to flex her foreign policy credentials and has stood out among her rivals for her steadfast support of Israel and Ukraine.

A trickier spot has been her hawkish stance on China. Ms. Haley’s stump speeches are laden with warnings that China is outpacing the United States in shipbuilding, hacking American infrastructure and developing “neuro-strike weapons,” which she says can be used to “disrupt brain activity” of military commanders and civilians.

But as governor of South Carolina, she lauded and welcomed Chinese companies that wanted to contribute to the state’s economy, helping those entities expand or open new operations. Those moves have opened her to attacks from Mr. DeSantis and other opponents, and she and Mr. DeSantis have lobbed false or misleading claims involving China at each other in recent weeks as the race for second place has tightened.

Explaining her position on the campaign trail, Ms. Haley has argued that her administration’s investments in Chinese companies accounted for a fraction of the jobs and projects spurred during her tenure, and that she had not been aware of the dangers China posed until she became U.N. ambassador. The threat of China has also evolved, she adds.

“There is not another governor in this race that hasn’t worked to recruit Chinese companies,” she said last month at a chapel in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. “Every governor has done the same thing, just like every one of you has Chinese products in your home.”

Identity politics

Few moments have defined Ms. Haley more in the public view than when she signed legislation to take down the Confederate battle flag at the South Carolina State House, after a white supremacist shot and killed nine Black parishioners in Charleston in 2015, including a state senator. On the trail, she powerfully recalls the experience, casting herself as a new generational leader capable of bridging divides.

But the feat also captures her calibration: As she ran for election in 2010 and then re-election in 2014, she rejected talk of removing the flag, a thorny issue in a state where Confederate heritage groups were a major political force. After the 2015 attack rattled South Carolina, Ms. Haley seized on the newfound political will among state lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

Ms. Haley has also wielded her own identity to significant effect. Much as she invokes her high heels to point out that she is the only woman in the race, she has used her family background to call for staunch immigration measures and her election as the first woman of color to lead South Carolina to argue that America is neither “rotten” nor “racist.”

Fighting the conservative cultural battles that have animated the G.O.P. base in recent years has not been central to her presidential campaign, but Ms. Haley has echoed Mr. DeSantis and Mr. Trump in some of her language criticizing gender and racial diversity initiatives in boardrooms and classrooms. Her stump speech incorporates nods to the growing wave of anti-trans legislation, and her call to end “gender pronoun classes in the military” remains one of her most reliable applause lines on the trail. At her education policy rollout in September, she joined a conservative political group known for promoting book bans, another cause adopted by many on the far right.

But as new polling has shown that the battle against “wokeness” has lost some of its political potency, her more recent remarks about education have tended to focus on support for school choice programs, which allow public money to be directed to private and religious schools, and tackling children’s low test scores in core subjects like reading and math.

Donald J. Trump

In the 2024 race, perhaps Ms. Haley’s most careful approach has been toward Mr. Trump, whose support among Republicans remains significant.

Not long after the assault on the U.S. Capitol, Ms. Haley said Mr. Trump had “lost any sort of political viability.” But she later went on to say that the party needed the former president and suggested that she would not jump into the 2024 presidential race if Mr. Trump decided to run. She then became the first to challenge him for the nomination — a move the Trump campaign highlighted in an email to supporters as one of her “flip flops” in the 2024 race.

In a January interview with the Fox News host Bret Baier, Ms. Haley explained her change of heart, saying conditions at the border, inflation and crime, and the country’s approach to foreign policy had worsened since she initially indicated she would stay out of the running. “I think we need a young generation to come in to step up and really start fixing things,” she said.

On the trail, she has alternated between criticism and praise of Mr. Trump. On the one hand, she has lauded him for his border policies. At the first presidential debates in August, she was among six candidates who raised their hands to indicate they would support the former president as their party’s nominee, even if he were convicted of a felony. But she also has called Mr. Trump “thin-skinned and easily distracted” — among her sharpest critiques — and more recently has been describing him as a force of “drama and chaos” that the country cannot afford.