What if These Economic Weapons Fall Into Trump’s Hands?

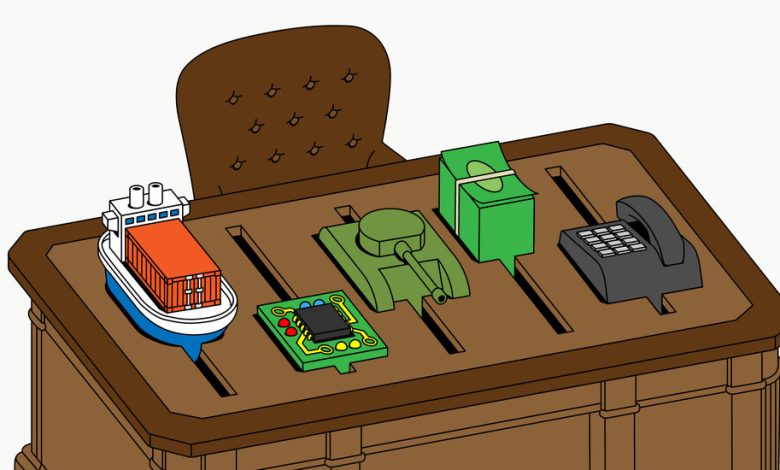

The Biden administration has built an unprecedented machine for economic and technological coercion. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the United States and its allies cut off Russia’s access to its own central bank reserves held outside Russia. The administration revamped export controls to strangle China’s access to the powerful and specialized semiconductors needed to train A.I., to keep its armed forces lagging on technology.

These economic weapons are far from perfect. As critics have noted, Russia is finding money in other places. China is already working around earlier export controls, although it won’t be able to produce its own cutting-edge semiconductors anytime soon.

But there is another problem, which is getting far less attention: Joe Biden will not always be president. These tools of coercion may work in the hands of the current administration, but they can also be used in far more dangerous ways in another, including one more reckless and unbound.

The Biden administration needs to think deeply about what future administrations can do with this power — particularly if Donald Trump takes up residence again in the White House in 2025 and repurposes Mr. Biden’s tools for his own aggressive purposes.

It’s hard to see the risks clearly, because Mr. Biden’s people have played it so calm. They realize that others might take fright at these newly powerful weapons, especially after what the Trump administration did with a more limited tool kit. At every stage, the Biden team has consulted with allies, patiently cooperating to ensure that everyone stays onboard. That helps explain why European companies like ASML have grudgingly been willing to limit sending cutting-edge chip manufacturing equipment to China.

The administration has even tried to reassure China. The national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, describes the approach as “small yard, high fence” — imposing heavy restrictions, but only on a small number of militarily important technologies. If the yard stays small, then the administration might counter China while minimizing economic damage.

But if Mr. Trump becomes the Republican nominee and wins next November, all bets are off. He prefers ferocious threats and grand, flashy gestures to measured economic strikes coordinated in partnership with allies. He doesn’t even consider them allies — when he was asked who America’s “biggest foe” was, he didn’t identify Russia or China first, but the European Union. As one European national security expert (and lover of 1990s Arnold Schwarzenegger movies) told us, a second Trump administration would be “T2” (a reference to the 1991 film “Terminator 2: Judgment Day”) — a far more effective killing machine than the relatively crude original.

What kinds of economic weapons might a different, more risk-tolerant administration deploy? Most obviously, it could repurpose Mr. Biden’s semiconductor measures to drastically escalate the U.S. confrontation with China. Robert Lighthizer, who served as Mr. Trump’s U.S. trade representative, has congratulated the Biden administration for doing an “excellent job accelerating” the use of export controls. Mr. Lighthizer also is already pushing Congress to adopt “aggressive” measures to decouple the United States and Chinese economies.

Instead of the small-yard approach, a second Trump administration might not limit its intrusion to just cutting off China’s access to specialized semiconductors for A.I. but could expand to a growing number of complex technologies. Mr. Lighthizer, for example, has proposed sweeping controls on U.S. investments in China, which would demand that businesses making technological investments tell the government that they are doing so; the government could then ban investments that it deemed harmful to “national or economic security.” This would most likely replace surgical strikes with indiscriminate bombardments, hitting U.S. companies with any but the most trivial investments in China.

Unconstrained economic war will ratchet up the prospect of tit-for-tat retaliation by China. Beijing has already threatened to restrict key materials needed to make semiconductors. One could easily imagine similar limits on the batteries and photovoltaics needed for the transition to a post-carbon economy. Even if this wouldn’t be effective, an economic gunfight between the United States and China would most likely leave the global economy as collateral damage.

The harsher the measures, the more everyone will try to work around them. China was already investing heavily in domestic semiconductor production before the confrontation. It is now redoubling its efforts as it tries to escape America’s grasp. Other countries, including allies, might be concerned that they will be the next target and distance themselves as well, and perhaps draw closer to China. Even if Xi Jinping is ruthless, he might seem less threatening than Donald Trump, who combines untrustworthiness with unpredictability.

That, too, could undermine U.S. security. The more easily China can attract other countries into its desired alternative world order, the more likely it is to feel comfortable in blockading or even invading Taiwan.

In a future Trump administration, potential nepotism in U.S. industrial policy, which could slow or limit successes in areas like chip manufacturing, and the accelerating decay of our body politic might slow down the spread of international chaos. But that is not the kind of guardrail one can rely on. Even if Mr. Trump doesn’t retake the White House, sooner or later, someone like him, who sees little value in restraint and alliances, is likely to.

We need to start building effective ways of putting limits on these economic measures now. This should start at home and build on one of the few elements of real bipartisanship — the recognition by both some Republicans and some Democrats that the president’s war powers go too far. A similar legislative coalition might be willing to curtail the president’s sweeping powers to undertake economic security measures without congressional review. Even if Congress has sometimes itself been far too quick to cheer on sanctions and export controls, this could ensure some transparency and accountability through public debate of proposed measures, limiting the likelihood of the most outrageous policy changes.

This needs to be augmented by international checks and balances. The Biden team has already started coordinating responses to Chinese coercion within the Group of 7. The administration should work to build stronger institutions and to clarify the international law on economic war, not to restrain just China but also its own possible successors.

And if it is unlikely that the United States can restrain itself, the administration may want to think about additional ways to empower others. Many of our allies have only started to work through the basics of using export controls or modern sanctions. Building their capabilities would provide another check on a belligerent China and insurance against an unrestrained United States.

Henry J. Farrell of Johns Hopkins and Abraham L. Newman of Georgetown are professors of international affairs and the authors of “Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.