The Essential Henry James

Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess.

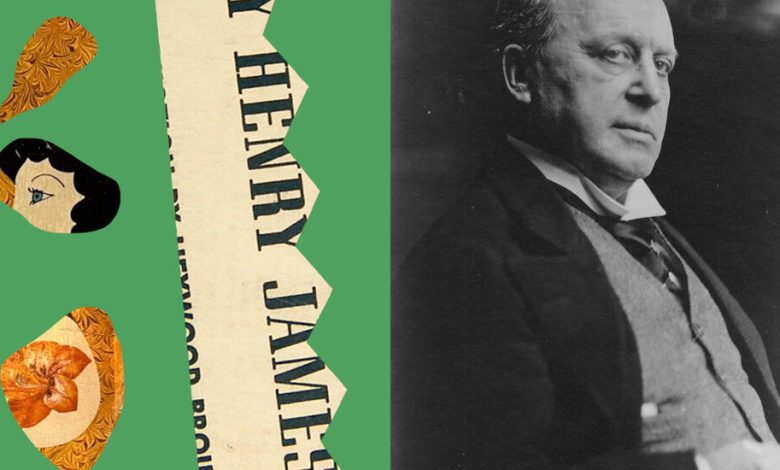

An American expatriate who spent his adulthood in England, James (1843-1916) was the patron saint of exquisite verbosity; of circuitous, compulsively sub-claused sentences that contain all the twists and adventures his story lines lack. Reading the prodigious body of fiction he produced over four decades, between 1871 and 1911, you get the sense he lost himself so deeply in his recurrent themes — the innocence of America versus the experience and depravity of Europe, the psychological richness of everyday life — that he couldn’t help carrying on.

This applied to his nonfiction, too. James didn’t just write novels; he wrote about writing novels, obsessing over his craft the way his characters obsess over the minutiae of their lives. Rejecting the “superficial” Dickensian novels of incident, James established himself as a student of George Eliot’s psychological realism, becoming a pre-Modernist forebear for writers from Edith Wharton to Virginia Woolf.

“The power to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things, to judge the whole piece by the pattern, the condition of feeling life, in general, so completely that you are well on your way to knowing any particular corner of it — this cluster of gifts may almost be said to constitute experience,” James wrote in his seminal 1884 essay “The Art of Fiction.” Where the historian dutifully records observed reality, he thought, the role of the novelist is to harness “impressions” into an imagined one.

The second of five children born to the theologian Henry James Sr. and the heiress Mary Walsh, James grew up moving between his native New York, New England, London, Paris and Geneva. His fiction would go on to reflect his trans-Atlantic upbringing as well as the influence of his older brother, William, the Harvard psychologist and author of “The Varieties of Religious Experience,” among other works.

James spent his later life dissecting the subtle dynamics between Americans abroad and the old-money Europeans they encountered there. Of his more than 20 novels, dozens of story collections and novellas and volumes of criticism, letters, essays and poems, these are the most essential books to read to understand the great legacy of Henry James.

Give me his indisputable best.

It is the book I have read more times than any other, even though — or because? — nothing much happens in it at all. At the start of “The Portrait of a Lady”(1881), a 21-year-old orphan named Isabel Archer is summoned from Albany to England, where she inherits her uncle’s wealth, receives and rejects two different marriage proposals and ultimately finds herself married to a widowed father, Gilbert Osmond, in Rome. Another expatriate who has lived in Europe since childhood, Osmond is both James’s receptacle for all the moral perils of continental society and his greatest villain.

That’s pretty much it. Isabel’s inward struggle between her independence and her affections, between the allure of centuries-old Italian splendor and the dark Roman shadows she begins to detect within, constitute the novel. And yet, the reader becomes so thoroughly rapt by her tortured, brilliant mind that this seemingly unremarkable young woman remains one of English literature’s most enduring heroines.

In a preface to the 1908 edition, James wrote of Isabel:

James’s 1908 prefaces to his various works are themselves a worthy treatise on literary theory, and this particular introduction persuades the reader to ignore any past and future critics who “still smirk at his willingness to grind near-nothings into powder,” as Anthony Lane pointed out in The New Yorker in 2012.

For its insistence on interiority over incident, its narrative and moral ambiguity, its ability to draw the reader so deeply into Isabel’s consciousness that we sincerely miss her after the final page, I recommend “The Portrait of a Lady” as not just the most important of James’s books, but one of the most important books, period.

I’d like to read James at the height of his powers.

James’s last big novel, “The Golden Bowl” (1904), is about a salacious love rectangle among the protagonist, Maggie Verver; her widowed father, a financier named Adam Verver; an Italian prince, Amerigo, whose family no longer has any wealth to speak of; and Maggie’s childhood friend Charlotte Stant. It was also, for the author himself, “the most composed and constructed and completed … the solidest, as yet, of all my fictions.”

As in his earlier work, the drama here is of the inward and domestic sort. What distinguishes this story is its tight focus on just four central characters, without the usual sprawling galaxy of lesser-drawn satellites.

“The Golden Bowl” was the third door stopper James published in just three consecutive years, following “The Ambassadors” in 1902 and “The Wings of the Dove” in 1903. In it, he spins an expertly tensile web of connections — father and daughter, husband and wife, old friends and extramarital lovers — overlapping in uncomfortably thrilling ways.

More big tomes, please.

Speaking of “The Wings of the Dove” (1903), this one had me yelling at the pages: Watching a pair of Londoners deceive our unwitting American heroine in an excruciatingly slow-burn fashion is almost too much for a sensitive reader to bear.

Milly Theale is an absurdly rich New York heiress who arrives in England with her middle-aged friend Mrs. Stringham. There they meet Maud Lowder and her love-stricken niece, Kate Croy, who has very little money and a raft of daddy issues.

Kate is in love with Merton Densher, a British reporter who charmed Milly during his previous travels to America. When they find out Milly is in poor health — the details of her illness remain mysterious throughout — Kate and Merton plot to deceive her into marrying him, so that he can inherit her wealth upon her death and then marry Kate.

Milly is, until a final act of heartbreaking command, among James’s most tragic and acquiescing protagonists, not because she lacks perspicacity or observation, but because of the frustratingly indefatigable goodness of her heart. This book is a culmination of James’s long suspicion that in Europe, the pure American conscience is doomed to encounter richly ornamented manipulation.

Freak me out!

Inspired by a real-life ghost story he heard from the archbishop of Canterbury three years earlier, James’s novella “The Turn of the Screw” (1898) holds up today as a genuinely chilling tale of haunted children at a sprawling country home in Essex. The orphaned children have been taken in by their uncle, who has given our unnamed narrator, their new governess, strict instructions never to bother him with the details of their upbringing.

When she arrives at the manor, one of her charges, Miles, has just been expelled from boarding school and returned home to his younger sister, Flora, and their sweetly naïve housekeeper. At first the narrator finds both children eerily well behaved, until she begins to suspect they are entangled with strange adult figures she sees roaming the property at a distance. The housekeeper confides that the estate had two former employees, Miss Jessel and Peter Quint, who were lovers, and who have since died.

This masterpiece of horror fiction evokes the timeless terror of childhood corruption while leaving so many questions satisfyingly unanswered.

Actually, I’d like a romp.

James’s second novel, “Roderick Hudson” (1875), was his first major one, and perhaps his most fun. A precursor to Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, Hudson is not so much the protagonist of the novel as the protagonist’s gilded object of affection. The Boston art patron Rowland Mallet (James got a bit heavy-handed with the name) scoops up Hudson from his small-time life as a law student and amateur sculptor in Northampton, Mass., and expands his horizons across Europe, where Mallet tries to coax a burgeoning talent to blossom.

Though it lacks the Gothic surreality of “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” “Roderick Hudson” predicts a similar trajectory for its title character, who becomes more and more fixated on beauty and pleasure and abundance until he falls, like Icarus, into ruin. The third-person omniscient narrator is often winking at the reader, pulling us into his confidence as we witness the inevitable implosion of aesthetic hubris. (The novel also introduces James’s endlessly alluring and enigmatic recurring character the Princess Casamassima, who got her own title in 1886.)

How about a hapless, male American entrepreneur?

James might as well have named Christopher Newman, the protagonist of “The American” (1877), Christopher Newmoney. The male counterpart to James’s rich and pliant American heiresses and the younger counterpart to those heiresses’ dynastic patriarchs, Newman is an unfamiliar breed of wealth for the continent. “I have been in business since I was 15,” he tells Madame de Bellegarde, a French aristocrat and his would-be mother-in-law. The precise nature of his commercialism is almost beside the point. (At one time there were bathtubs; at another, leather.) The point has been to work very hard and to get very rich.

He succeeded, but all that happened before the start of this novel; James is more interested in the granular social implications of that entrepreneurship than he is in the mundane details of global trade. Having embarked on a European tour with the vague aims to “see more of the world” and to be “deliciously lazy,” the 30-something retiree meets a young widow named Claire de Cintré in Paris, and stops in his proverbial tracks.

The crux of James’s roiling drama is that the Bellegardes are as tempted by Newman’s millions as they are put off by the idea that those millions were self-made. The ending promises a soap-opera scandal and a hunt for blackmail, Newman’s New World morality transmuted, in the Old World, into its opposite.

I want to learn about James himself.

For those interested in James’s somewhat shrouded personal life, two biographies, the updated and abridged edition of Leon Edel’s five-volume “Henry James: A Life” and Michael Gorra’s “Portrait of a Novel: Henry James and the Making of an American Masterpiece” (2012), offer all the demystifying details, and then some.

Edel won both a Pulitzer and a National Book Award for his series, which was published between 1953 and 1972 and remains perhaps the manual for James scholarship and for anyone interested in the craft of biography more broadly. Even the condensed version covers plenty of ground. It is a 750-page survey of James’s nomadic childhood; his early and unfinished law studies at Harvard; and his relationships with William and especially his younger sister Alice, who died of breast cancer in her 40s, leaving James bereft. And it touches on his permanent relocation to England and exposure to his great European inspirations, among them George Eliot, Gustave Flaubert and Ivan Turgenev.

This version, which Edel edited in the 1980s, also contains necessary revisions to his treatment of James’s possible homosexuality, which the biographer came to consider “excessively indirect.”

Gorra’s book, a Pulitzer finalist, has two subjects: “The Portrait of a Lady” and its author, weaving textual analysis with biography and history in a mesmerizing work of literary scholarship.

The novelist Colm Tóibín makes no qualms about approaching the issue of James’s sexuality in his fictional biography, “The Master,” which spans five years before the turn of the century, when James was at the height of his powers, and perhaps of his self-doubt.

Tóibín treats James the way James treated his own characters, boring a deep hole into his brain and inhabiting it with relish. Like any novel, particularly one by James himself, “The Master” opens a window onto aspects of individual life that are no less true for their being presented in fiction.