That Time Europe Tried to Bring Monarchy Back to Mexico

HABSBURGS ON THE RIO GRANDE:The Rise and Fall of the Second Mexican Empire, by Raymond Jonas

In October 1863, a Mexican delegation arrived in Trieste, a polyglot city in southern Europe on the borderlands of the Hapsburg Empire. In a turreted castle on the Adriatic coast, the delegates — many of them Europhile bankers and industrialists — offered the crown of Mexico to Maximilian, a Hapsburg prince, and his wife, Charlotte, daughter of the king of Belgium.

Since gaining independence in 1821, Mexico had squandered the “splendid legacy” of European rule, the delegates explained, and the country now led a “sad existence” as a shaky, vulnerable republic. Only the resurrection of monarchy could guarantee stability and prosperity. The timing was crucial. Mexico’s republican neighbor, the United States, was too preoccupied by a civil war to block European intervention.

Maximilian thought of himself as a progressive monarch; he would accept the invitation only if it represented the true will of the Mexican people. When the delegates returned the following April, they brought enthusiastic testimonials from towns and villages across Mexico. Satisfied, flattered and ambitious, Maximilian and Charlotte set sail for North America as the emperor and empress of Mexico.

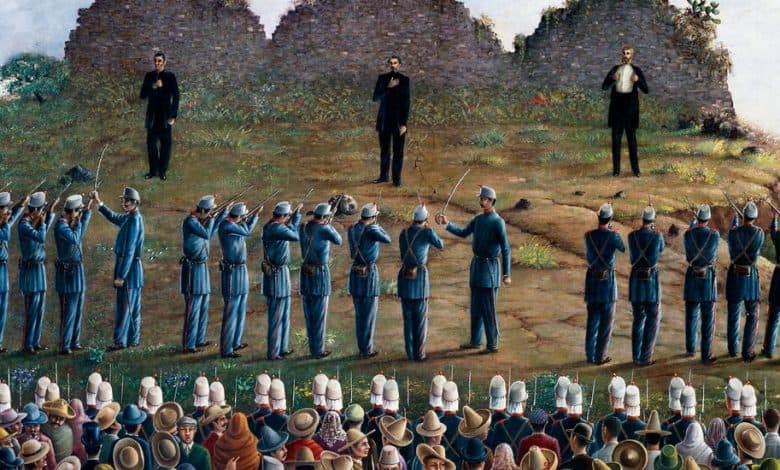

Two years later, a shattered Charlotte was back in Europe, eating nothing but fruit she peeled and nuts she shelled herself for fear of poisoning. Maximilian would soon be dead, executed by Mexico’s republican forces on a rocky hillside outside Querétaro.

The rise and fall of the Second Mexican Empire is the subject of “Habsburgs on the Rio Grande,” by the historian Raymond Jonas. Seen from the American perspective, Maximilian’s fleeting rule is all too easily understood as a European fantasy that failed to grasp history’s ineluctable path from monarchy to democracy. Jonas instead argues for its global significance, placing it at the center of a transcontinental power struggle between an expansionist United States and faltering European supremacy.

When Mexico first cast off Spanish rule, the country established its own independent monarchy — the First Mexican Empire — and then, in 1824, a republic. Two decades of turbulent constitutional change and civil strife followed. In 1845, the United States annexed Texas from Mexico. It then launched a war of aggression that would strip Mexico of half of its territory. U.S. ambitions appeared unlimited, its appetite for territory insatiable, and many Mexicans feared their young republic would succumb entirely.