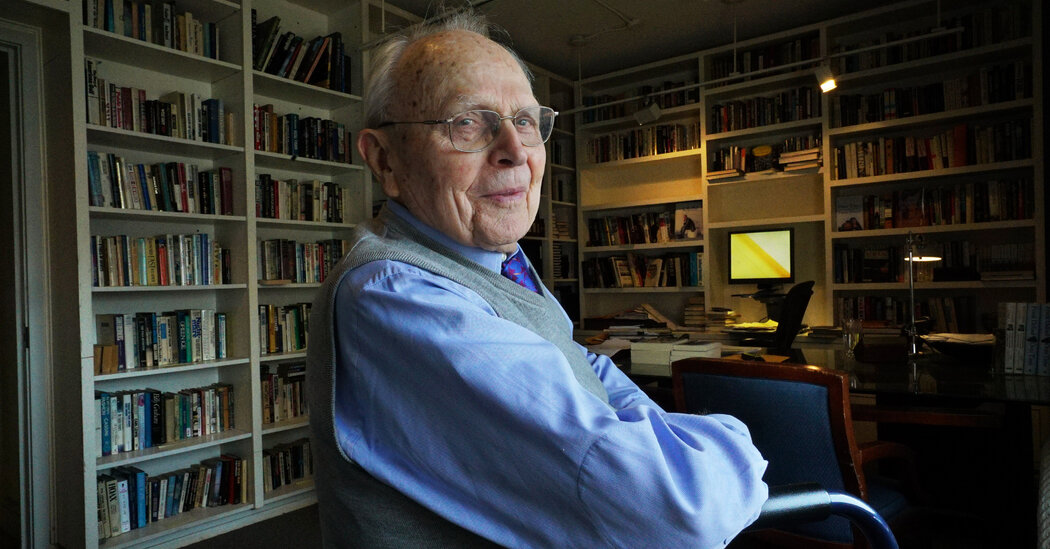

Sterling Lord, Premier Literary Agent, Is Dead at 102

About 10 years ago Sterling Lord invited four long-term clients of his for lunch at the Regency Hotel in New York. As a matter of longevity, at least, it’s pretty safe to say that no other literary agent anywhere at any time could have assembled such a group.

Mr. Lord had represented one of them, the sportswriter Frank Deford, for 53 years, and another, the investigative reporter and sometime novelist David Wise, for more than 60. A third author on hand that day, the writer Nicholas Pileggi, had been a client for at least 50 years. The baby in the group was the political analyst Jeff Greenfield. Mr. Lord had represented him for a mere 44 years. All told, when they toasted Mr. Lord that afternoon, it was for more than two centuries of representation.

“It was an amazing moment,” recalled Mr. Pileggi, the author of “Wise Guy,” a book for which Mr. Lord hatched the idea, and which Martin Scorsese adapted for the 1990 movie “Goodfellas.” “Here we were, all at an advanced age, and we were still the kids Sterling was helping.”

For Mr. Lord, who died on Saturday in Manhattan at 102,such steadfastness was standard. For more than 60 years he was one of New York’s most successful and durable literary agents, representing Jimmy Breslin, Art Buchwald, Willie Morris, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Howard Fast, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gordon Parks, Edward M. Kennedy, Robert S. McNamara and the Berenstain Bears, among many others.

Joe McGinniss, for whom Mr. Lord handled the celebrated 1969 study of the marketing of Richard M. Nixon, “The Selling of the President 1968,” said in an interview for this obituary in 2013, a year before he himself died: “Sterling’s career encapsulated the rise and fall of literary nonfiction in post-World War II America. He was the last link to what we can now see not so much as a Golden Age, but as a brief, shining moment when long-form journalism mattered in a way it no longer does and may never again.”

It was for his association with another writer, Jack Kerouac, and Kerouac’s book “On the Road,” that Mr. Lord will most likely be remembered most, though his claim there is disputed.

Mr. Lord was a fledgling Manhattan literary agent in 1952 when, by his account, Kerouac walked timidly into his office, a basement studio on East 36th Street, just off Park Avenue. Though nearly the same age — Kerouac was 29 at the time, Mr. Lord two years older — the two men shared little else; Mr. Lord was an urbane man who favored jackets, foulards and tennis whites, spoke almost inaudibly, and had no apparent vices. Kerouac was a rough-hewed, hard-drinking New Englander who hung around with the Beats.

Inside Kerouac’s weather-beaten knapsack and wrapped in a newspaper, Mr. Lord recalled, was a manuscript that Kerouac handed gingerly to him. It took Mr. Lord four years to sell the book, for a measly $1,000. But at last count, “On the Road” has sold five million copies and burned just as many gallons of gas as generations of young people have set out in search of either the America Kerouac saw or the ones that have taken its place.

Mr. Lord’s tennis skills — he had played since he was 5 years old, was nationally ranked as a teenager and in 1949 took the French national champion Marcel Bernard to five sets — proved a great asset, bestowing on a small-town Iowan a confidence that he might otherwise have lacked. It also gave him a leg up on snootier agents who may have tossed their newspaper sports sections. Many of Mr. Lord’s biggest books — Peter Gent’s “North Dallas Forty,” Bill Nack’s “Secretariat,” Pete Axthelm’s “The City Game” — grew out of that sports world.

Then there was his perfect moniker. “What was your name before you changed it?” a friend once asked Sterling Lord. When a book he had handled came out in Portuguese, an unwitting translator rendered the grateful author’s dedication as “to the Supreme God.”

Sterling Lord was born in Burlington, Iowa, on Sept. 3, 1920, the son of Sterling and Ruth Towne Whiting Lord. His father, a furniture executive, was also an amateur bookbinder and nourished in his son a love of books. It was a passion that Mr. Lord sated vicariously, for he was no writer: For years, his only book was on tennis, “Returning the Serve Intelligently.” (His own tennis serve was said to resemble a knuckleball, and to be just as hard to hit.) In 2013 he published a memoir, “Lord of Publishing,” to little notice.

After graduating with a degree in English from Grinnell College in Iowa, Mr. Lord was drafted into the Army and shipped to Europe near the end of World War II. When the fighting stopped, he helped edit the weekly magazine of the military publication Stars and Stripes; when the Army dropped that publication in 1948, he and a colleague briefly ran it privately, first out of Frankfurt, Germany, and then Paris, where Mr. Lord adopted the dapper dress that became his signature. When the magazine closed in 1949, he moved to New York.

Over the next few years he either worked on or edited several magazines, including True and Cosmopolitan. Those experiences convinced him that literary agents were not serving magazine writers well and that they had failed to spot changes in the postwar literary marketplace. Americans, including millions of former G.I.s, were suddenly more mobile, less provincial and less interested in escapist fiction than they were in understanding the world around them.

One early client was Al Hirshberg, who ghostwrote “Fear Strikes Out,” Jimmy Piersall’s memoir of baseball and mental illness. Another was Rowland Barber, who helped the silent Marx brother write “Harpo Speaks!”

Mr. Lord persuaded HarperCollins to pay $3.2 million to lure the Berenstain Bears children’s books from Random House. He got Erica Jong $1.2 million for her novel “Fanny” and Judge John J. Sirica $500,000 for the paperback rights to his Watergate memoir.

Rarely, he boasted, did he scour for clients, let alone steal them as others were increasingly wont to do. His old-fashioned ways extended even to his letterhead, which listed his telephone number as “Plaza 1-2533.” “If you didn’t know New York City was 212, he really didn’t want to hear from you,” said Stuart Krichevsky, a fellow agent who worked with Mr. Lord for 16 years.

In 1987, Mr. Lord joined the agent Peter Matson to form Sterling Lord Literistic. Mr. Lord gradually yielded day-to-day management and eventually sold his stock. But he continued to work, and into his 90s remained the highest-earning agent in the office.

His last years with the agency were unhappy, however, as he came to feel that some of his colleagues were undermining him. In 2019, though suffering from the macular degeneration that had stopped his tennis game, he set up a new literary agency on his own.Mr. Lord’s death was confirmed by Philippa Brophy, the president of Sterling Lord Literistic.

Mr. Lord was married and divorced four times. He is survived by a daughter, Rebecca Lord.

According to Mr. Lord, Kerouac had come to him at the suggestion of Robert Giroux, then at Harcourt Brace. Mr. Giroux had not quite rejected “On the Road,” but he wouldn’t handle it in the form in which Kerouac had famously written it and tendered it to him: on a 120-foot scroll of architectural tracing paper.

Mr. Lord found the book fresh and distinctive. But it took him so long to sell it that a discouraged Kerouac asked him to pull it off the market. Mr. Lord ignored him.

Mr. Lord’s partner at the time, Stanley L. Colbert, later claimed that things went down very differently. In a 1983 article in The Globe and Mail of Toronto, Mr. Colbert said that it was to him that Mr. Giroux had sent Kerouac, and that it was he who had first spotted him — “an imperfect body with neck too long and legs too short” — in the office doorway. At his side, he said, on the floor, was a “dog-eared manuscript tied together by thick clothesline knotted furiously at the top.”

Far from encouraging him to pursue the matter, he added, Mr. Lord “berated me for wasting my time on transients, bums and has-beens.” Mr. Colbert said that it was he who had sold “On the Road” — to Malcolm Cowley at Viking Press — and that once he had, he told Mr. Lord to “take the business and his attitude and shove it.”

What is beyond dispute is that Kerouac stuck with Mr. Lord. He not only continued to represent Kerouac but became his friend — Kerouac came to call the guest quarters of the home he shared with his mother in Florida “the Sterling Room.”

But Mr. Lord proved powerless to halt Kerouac’s decline into alcoholism and drugs, during which Mr. Lord would sometimes spring for his groceries. “Fond as I was of Jack, I was only his literary agent, not his life agent,” he wrote.

When Kerouac died in October 1969, Mr. Lord was at his funeral, both incongruous — “natty as ever in his blue shirt with the white collar and a dark necktie,” as the Beat writer and historian John Clellon Holmes later wrote — and at home amid the aging Beats, youthful acolytes and assorted locals gathered at a Roman Catholic church in Lowell, Mass.

Mr. Lord didn’t keep his original manuscript of Kerouac’s “On the Road,” nor did he ever procure a signed copy for himself. “I wasn’t thinking of it; I was thinking of helping Jack,” he said in an interview for this obituary in 2013. He wished he had, he allowed, noting that an autographed copy of “On the Road” would have been worth $20,000 at the time. But he quickly added a caveat: Never, he said, could he have sold it.

“I’m in a business that is absolutely captivating,” Mr. Lord told Publishers Weekly in 2013, 61 years after entering it. “It’s enabling me to live forever.”

Jack Kadden contributed reporting.