Review: Finding a Collective Groove in Church and in House Dance

“In the beginning, God had a groove. And from that groove came the groove of all grooves.”

Those lines, spoken by Reverend CJ (Carl Robinson Jr.) in a new dance by the choreographer Rennie Harris, refer to the opening of a classic house song, “Can You Feel It” by Mr. Fingers (Larry Heard): “In the beginning there was Jack, and Jack had a groove.”

And if any dance artist could groove out a church, it would be Harris, the hip-hop master who has become one of the most exacting and exciting choreographers of his generation.

In “Lifted: A Gospel House Musical,” Harris — celebrating the 30th year of his Philadelphia company, Rennie Harris Puremovement — delves into spirituality by way of Charles Dickens’s “Oliver Twist.” It’s a look at redemption, in which Harris’s imagination and heart are displayed side by side.

“Lifted,” making its New York debut at the Joyce Theater on Tuesday, includes a stirring gospel choir (Alonzo Chadwick & Friends); propulsive music layered in moments with voice-overs (by the composers Raphael Xavier and Darrin Ross); and dancers from Harris’s company as well as the Hood Lockers, a crew of four spry veterans — Richard Evans Jr., Joshua Polk, Andrew Ramsey and Marcus Tucker — who portray church ushers and a gang called 40 Thieves.

There’s a lot going on. Told in six sections, “Lifted” begins at church where we are introduced to Joshua (Joshua Culbreath), an unhappy orphan living with his aunt and uncle. An argument ensues among them, which we grasp not through words but images: Raised arms, imploring eyes and, for Joshua, a particularly pained exasperation as he covers his face with his hand.

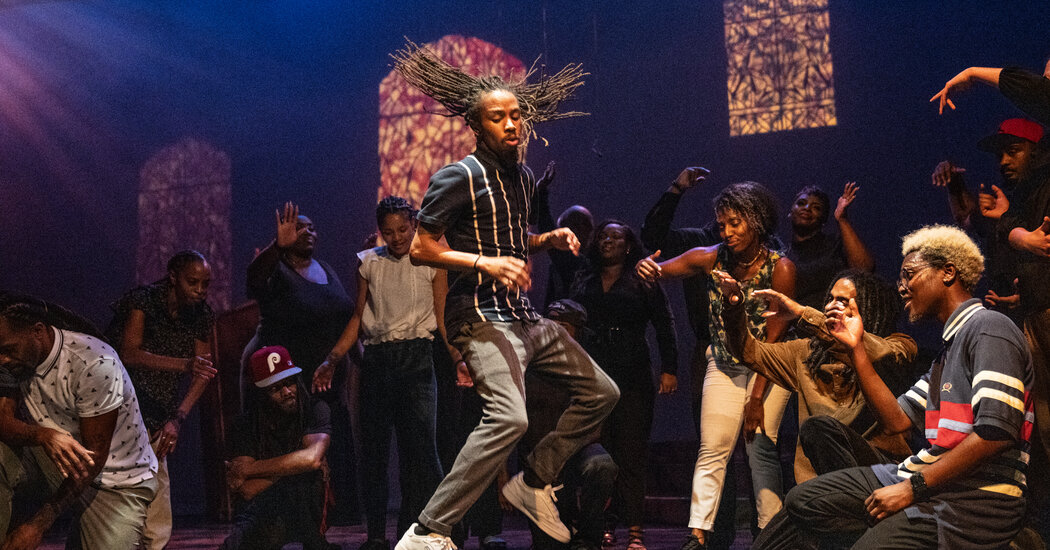

Churchgoers fill the space, walking in slow-motion and stuttering to a halt as the argument between Joshua and his relatives is replayed, but backward, like a videotape rewinding. Eventually the ensemble erupts into a passage of cascading, fast footwork that spills and slides over the stage in a thrilling feat of ease and acceleration. Here, are two sides of Harris’s rhythmic wizardry; both are impeccable.

At times, though, the storytelling in “Lifted” feels ragged, a problem amplified by a spotty microphone system that muffles dialogue, some of it wryly funny. Certain parts land stiffly, with the vibe of an after-school special. Yet throughout, the music and dance are something to behold, and Harris’s poetic insight into the interior and exterior worlds of his characters is continually vivid. It’s not just his decades-long work in hip-hop and street dance that brings such a vibrant lucidity to rhythm and the dancing body, but the way he gives virtuosity a sense of theater, of form, of feeling.

That is most apparent in a poignant scene in which Robinson sings “I Need You Now” by Smokie Norful as Culbreath performs a breathtaking solo that sends his lithe, slender body flipping into the air, spiraling on one side and then the other, pausing every so often for awe-inspiring balances. This is more than technical prowess; Culbreath pours his emotions into a physical state. He wrings himself out and, by the end, seems less a person than a spirit.

But Joshua is still struggling. He falls in with a group of pickpockets led by Big Poppa (Rodney Mason), an aging street thug who is tough but also, somehow, still just a little boy — especially when he confides his love for Underoos and the Superman bottoms he still secretly sports. “They make me feel like a king,” he says, before adding ominously, “but why be a king, when you can be a god?”

He orders Joshua to rob the church, but Joshua can’t go through with it and instead turns to the church to heal his pain.

Harris develops his take on gospel house as he elevates club culture to a higher spiritual realm. The club, like church, is a place for communal worship, just as the song “Can You Feel It” says that house music is for everyone.

In “Lifted,” understanding the weight of that collective groove is crucial. What, to Harris, is movement all about? It is intelligence, agility, rhythm — the body’s ability to engage in a ritual, one of perpetual motion. Dancers come together like a choir. When, near the end, Joshua twists his body into a frenzy and spins to a halt with a finger pointed in the air, a voice-over says: “I am no longer willing to be this pawn in the game that lives outside myself so I dance. I dance. And I choose to be free.”

It seems like “Lifted” is over. But after the cast takes its bows — cleverly gliding in and out of the choreography to do so — there is a more ominous moment. The performers converge on a darkened stage as snippets of somber news reports flicker on the projection of a stained-glass window. Suddenly, Big Poppa appears: Taking a deep breath he blows on them, as if he extinguishing the candles on a cake.

It’s an unsettling coda, similar to the ending of “Lazarus,” Harris’s celebrated 2018 work for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. In a way, “Lifted” and “Lazarus” feel like companion pieces; neither ends happily, but rather looks at the world for what it is. You can dance your heart out, but you can’t escape reality.

Lifted: A Gospel House Musical

Through Sunday at the Joyce Theater; joyce.org.