My Grandfather’s Death Party Was a Final Gift to His Family

My grandfather liked to stage a scene. He moved to California in 1935 to work in Hollywood, becoming a director for B-list movies and TV shows like “77 Sunset Strip” and “The Mickey Mouse Club.” Despite his work, he didn’t particularly care for film and didn’t own a TV until 1964. Even then he mostly used it to watch Dodgers games. What he liked was the process of making a show: reworking the script, setting the angles, being in charge.

Like so many in his generation, he was a multipack-a-day smoker; a Philip Morris cigarette hangs from his lower lip in nearly every photograph I have of him. He lived with emphysema for decades, maintaining his last sliver of healthy lung tissue through a combination of lap swimming, walking, Scotch and luck. But at 97 years old, he had flagging energy. No longer able to walk from his bedroom to the kitchen without stopping to catch his breath, he rigged up an oxygen tank that allowed him to roam the length of his home. Tubes followed him up and down the corridor.

Death is, famously, one of the few certainties in this life. It’s also a reality that doctors, patients and families tend to avoid. In a recent report, The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death notes that today death “is not so much denied but invisible.” At the end of life, people are often alone, shut away in nursing homes or intensive-care units, insulating most of us from the sounds, smells and look of mortality.

Not so for my grandfather. Though he didn’t rush headlong into the hereafter, he didn’t want to wait for his faculties to fail one by one. He wanted to die with a modicum of independence, with hospice care.

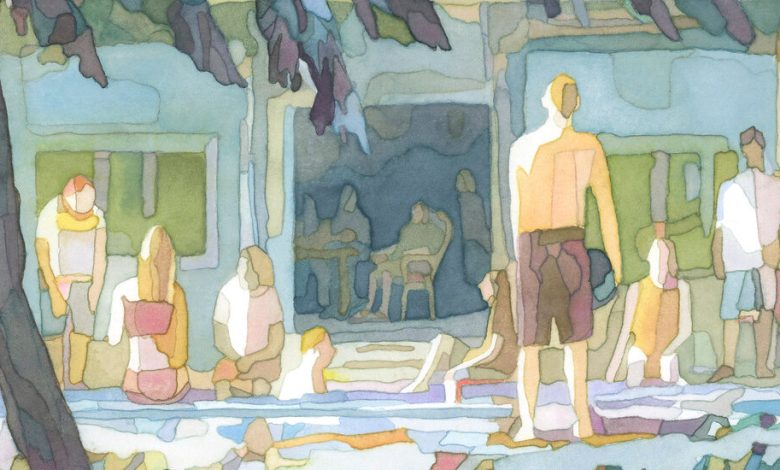

On an unseasonably warm Los Angeles day in May 2011, a cast of characters — his children, grandchildren and friends — assembled at his home, ready to play their part in the last act of his life. I was a college junior at the time, required to read Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” for class that week. I found it in an English poetry collection of my grandfather’s and read sitting on a sagging couch, intermittently distracted by family members who, one by one, came in and asked what I was doing. They’d smile and recite the opening lines: “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan/A stately pleasure-dome decree:/Where Alph, the sacred river, ran/Through caverns measureless to man/Down to a sunless sea.”

What ensued was a five-day tropical vacation. My grandfather couldn’t stand the air-conditioning, so we wore bathing suits most of the day and paged languidly through withered photo albums. I floated in the sacred waters of my childhood — the swimming pool — and harvested lemons from the prolific backyard tree. When 6 o’clock rolled around, my grandfather would ask, “Who’s pouring me a Scotch?” Cocktails, cheese, olives and stale water crackers appeared. We listened to classical records and told stories and took turns cooking dinner. But just as Coleridge’s vision faded, interrupted by a person from Porlock, our reverie was splintered by closed-door meetings with hospice nurses and conversations with doctors, who could attest my grandfather had a sound mind and a failing body and was eligible for end-of-life care.

However perverse it may sound, that death party — as my sister and I came to call those five days — remains one of the most profound experiences of my life. For a brief moment, at my grandfather’s party, I got to slow down the inevitable, to be with the people I grew up with, in the place we held sacred and dear. Amid that joyful reverie, I had time to sober up and confront the simple reality that my grandfather wanted to die and that everything would change. I saw that the man who had commanded movie sets and TV crews now rarely left his house. That his sweaters hung loose on his stooped shoulders, and that his rosebushes withered with neglect. That things were already changing, whether I was ready for it or not.

People often talk about death as if it’s the worst thing that can happen to someone. As if it’s something that must be avoided at all costs. Better to age, however painfully, however diminished, than to ever admit that we are mortal. But at the end of a long, full life, my grandfather was done. He died with power and agency, love and support. To have that death, he had to acknowledge and embrace his mortality. At our death party, he gave his family a chance to accept that fact, too.

More than a decade later, my parents are discussing their own plans, debating whether to be cremated or buried. My dad calls to talk about what I want. Would I visit their grave sites? Would that be meaningful? There are no monuments for my grandfather, whose body was eventually cremated and scattered at Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles. When I miss him most — when I married, or when my nieces were born — I pay homage with a cocktail, a toast and a memory. I think about one evening during the party when, as the room hummed with humans, he held my head in his hands. A few days later, he had his usual Scotch, went to bed and died. In my memory, this moment — the moment when we looked at each other, when we said I love you and when we let each other go — lives on. It comforts me when I pass through caverns of sadness and am marooned in sunless seas of grief. I tell my parents I don’t need them to have a grave site.

Sara Harrison is a writer and journalist. Her work has appeared in Wired, New York magazine and other venues.