I’m Going Blind. This Is What I Want You to See.

Supported by

Continue reading the main story

I’m Going Blind. This Is What I Want You to See.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article -

5

- Read in app

Video by James Robinson

Mr. Robinson is a filmmaker.

“Adapt-Ability” is an Opinion Video series inviting you to confront discomfort with disability.

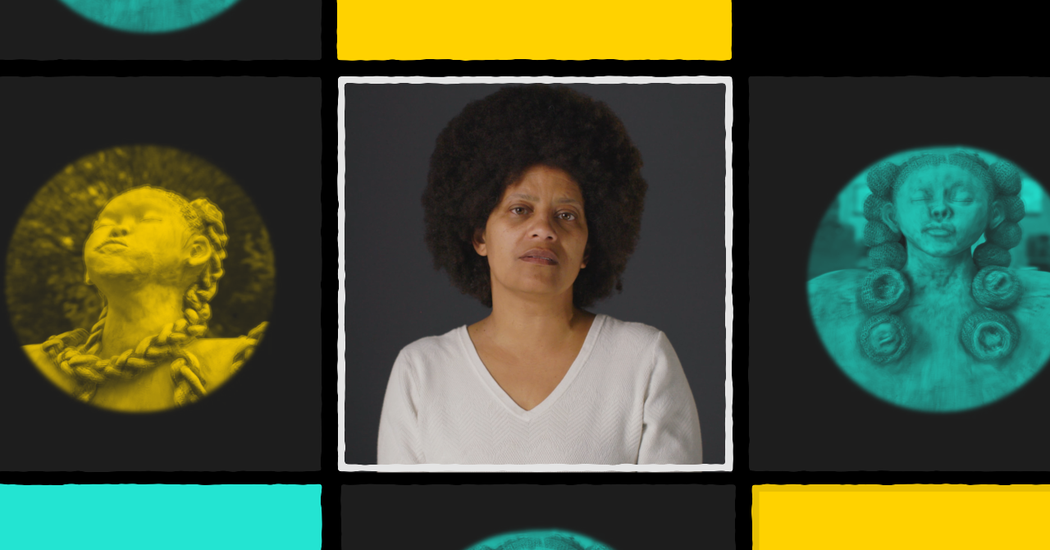

In the Opinion video above, the filmmaker James Robinson introduces us to Yvonne Shortt, who is legally blind. But unlike the stereotype of the blind living in a lightless world, Ms. Shortt, like most other legally blind people, lives a nuanced existence between those who see well and those who can’t see a thing.

Ms. Shortt has retinitis pigmentosa, a disease that causes progressive loss of sight. She can see some things some of the time, depending on various factors, including the amount of ambient light, her distance from the object and the object’s location in her field of vision.

In this short film, Mr. Robinson simulates what it’s like to be Ms. Shortt, navigating her world with progressively declining eyesight but also recognizing what she has gained even as she has lost something so precious.

transcript

I Have Whale Eyes. You Can Still Look Me in the Eye.

A filmmaker devises a few experiments to help his family experience his disability — and show how a little imagination can make us all more empathetic.

[MUSIC PLAYING] I have a question for you. Is the red dot inside or outside of the white box? “OK, I do not see a red dot.” “What red dot?” “I don’t see the red dot.” “There’s no red dot.” OK, I’ll do it again. Is the red dot inside or outside of the white box? “I don’t see a box.” “There’s no white box.” “So now I see the dot, and I see no box.” Next one. “Oh, I see what you’re doing. What?” “Is this what it’s like for you? Oh, God.” That’s what I see when I take the test. “Oh.” [MUSIC PLAYING] Nature has located the eye close to the brain so that its messages may arrive there quickly. The eyes are really an extension of the brain, and the whole optic system is capable of understanding and memorizing. Are my eyes [expletive] up? “They are a little bit.” “Nothing’s wrong with your eyes. They’re just different.” “Your eyes are different from other people’s eyes. I think only you know if they’re messed up. Certainly, people from — who see you think they’re messed up.” Do my eyes make me uglier? “I wouldn’t say so.” “No. I mean, I don’t know.” “No, you have beautiful eyes, I guess. I think so. What color are they? Brown?” I’m your child. So, my name is James, and these are my eyes. Having eyes like mine, well, it feels like everyone I meet is frolicking happily on the ship they’ve dubbed the U.S.S. Normal. And then here I am, below the surface, feeling a bit isolated. But whenever I get up near the surface, where the people on the U.S.S. Normal can see me, everyone starts acting a little weird. They get nervous. They don’t know what to do, so they just avoid looking into the ocean altogether. Even my own family. What is wrong with my eyes? “I don’t exactly know, but one of them is — you have a lazy eye.” But I don’t have a lazy eye. My brother has sat across from me at the dinner table for his entire life. In that whole time, he never got up the courage to ask me what was happening with my eyes. Now, look, I get it. I used to also believe that this conversation was best avoided. I used to lie to people about the name of my condition, telling them that it was a lazy eye. Not because this was true but instead because it was something that they would have heard of. But the thing is, I don’t really think that’s productive anymore. And that’s why we need to talk. If you’re going to spend your whole life aboard this ship, then I want to tell you a little bit about how you can meaningfully interact with what else is out there in the ocean. You see, the name of my condition is strabismus. I’m an alternator with exotropia, and I have a complication called A.R.C. All of that is hard for even me to remember. So that’s why, a couple of years ago, I just started calling them whale eyes. We take our type of vision for granted, but consider the case of the whale. What was it like to give birth to a whale? “Oh, God. I did not know that you were a whale at the time.” For me to explain whale eyes to you, the first step is to understand how normal eyes work. “Normal” is a complicated phrase. My mom is technically normal. Her eyes both work together. But she’s also the proud owner of a 50-pound bag of popcorn kernels, which is exclusively for personal consumption. Well, let’s say you wanted to look at this abnormal object with your normal eyes. A normal person would see the popcorn out of both eyes. “Your brain fuses those two images into one, and you figure out 3-D.” That 3-D is how we do things like shake hands, play Ping-Pong and hand each other Post-its without missing. “So that’s considered normal? Your eyes —” Yeah, kind of a different story over here. You see, what happened is both my eyes worked perfectly individually. They can both see the popcorn with 20/20. It’s just that this collaboration stage where they got a little confused. So my brain was getting this image from the left eye and this image from the right eye. And it was like, holy cow, that is so much information and so much popcorn. My brain could only handle one of these at a time, so I started switching back and forth. You see, my eyes were never actually lazy. It was just my brain got confused. [MUSIC PLAYING] In the U.S., as soon as you’re born into the ocean of difference, people try to start fishing you out. And believe me, I tried it all. Band-Aid eye patches, pirate eye patches, staring at strings for long periods of time, 3-D glasses, reading glasses, staring at strings for even longer periods of time. The most popular form of vision correction is surgery. If you’re young enough, doctors can straighten your eyes and trick them into realizing that these two objects are actually the same thing. I had it twice, and the doctor missed both times. This is what missing looks like. The eyes might look aligned, but it wasn’t close enough to trick my brain. I was like a fish that kept getting caught, taken into a boat and then wiggling its way back into the ocean. What all these failures meant is that I was going to have to grow up with whale eyes, overboard in the sea of difference. Let me give you an example from when I was 6 years old. I’m on the baseball team — Monte Cassino, Tulsa, Okla. So the coach would pitch you two balls, and you would try to thwack them. And if you couldn’t thwack them, which I never could, then you would get a tee, and you got two tries on the tee. And, obviously — I mean, if the ball is just sitting there on a stick, everyone hits it the first time off the tee. Almost everyone hits it the first time off the tee. I got my two chances, and I missed both times. [MUSIC PLAYING] And I remember the umpire didn’t know what to do because he had clearly never seen someone strike out in tee ball. My strikeout was just one of thousands of humiliations in which others didn’t know how to react to my whale eyes. We put so much time and effort into making sure that people who are perceived as different understand what it would be like if they were normal. But we rarely ever do the opposite. Pushing those who see themselves as normal to understand what it would be like if they were different. [SPLASH] Do you know what happens when my eyes switch? “You see out the other eye? I don’t know.” That’s a good start. But everything moves. “Everything moves?” Yeah. “Really?” [MUSIC PLAYING] So everything jumps. So when you’re reading, you’ll be like, the little brown fox jumped in the big black car. It’s like car is over here now. Now, my way of perceiving the world might seem strange and frustrating to you. But if you come below the surface, you’ll see that I’ve adapted. Take, for example, the pencil test. “Isn’t there are a famous article on pencils?” You close one eye, take two pencils, hold them out in front of your face and then try to touch the tips or the erasers to each other. “I can’t do it.” “Hands up. I got it.” Wow. Faster than any of us. “I know. Do you know what I do?” What? “You just look for the shadow.” I’ve taught myself to adapt. In all honesty, I don’t have a problem with the way that I see. My only problem is with the way that I’m seen. I just want to be able to connect with people. It’s hard to tell where I’m looking. I get it. It’s not just, “Where is he looking?” It’s like, “Where is he?” I’m still here. You just are having trouble connecting to that person. You want to know why I call them whale eyes? It’s because we love looking at whales, and we’re completely unbothered by the fact that we can only look into one of their eyes at a time. That’s the kind of acceptance that I’ve always craved. But I’m not a whale. And this whole thing about the sea of difference, it’s just a metaphor. I really live in your world. It’s a world of handshakes, and pitchers and rain. I have a fear of umbrellas. I always think they’re going to hit me. It’s a world of high fives and changing lanes and really sharp knives. That’s why I buy the precut cheese. And, yes, it’s even a world where children dream of the major leagues, even after striking out in tee ball. It’s because I really live in your world that I need your help overcoming this distance between us. That means looking back into whichever eye is looking at you and meeting those inevitable gaffes with patience. More than anything, what I really hope you’ll understand is that what for you is a few seconds of discomfort, for someone else is just one in a lifetime of little moments that have made them feel like they’re hundreds of meters below the surface, even though they’re really just standing a few feet in front of you, waiting to connect. [MUSIC PLAYING]

A filmmaker devises a few experiments to help his family experience his disability — and show how a little imagination can make us all more empathetic.

This is the first in a three-part series of videos by Mr. Robinson, who made “Whale Eyes,” a short Opinion film published last year that was nominated for an Emmy Award, about his own disabling eye condition. “Adapt-Ability,” an Opinion Video series, explores how it feels to live with a disability, and the ways in which society can adjust to be more inclusive of people with disabilities.

James Robinson (@ByJamesRobinson) is a filmmaker.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.