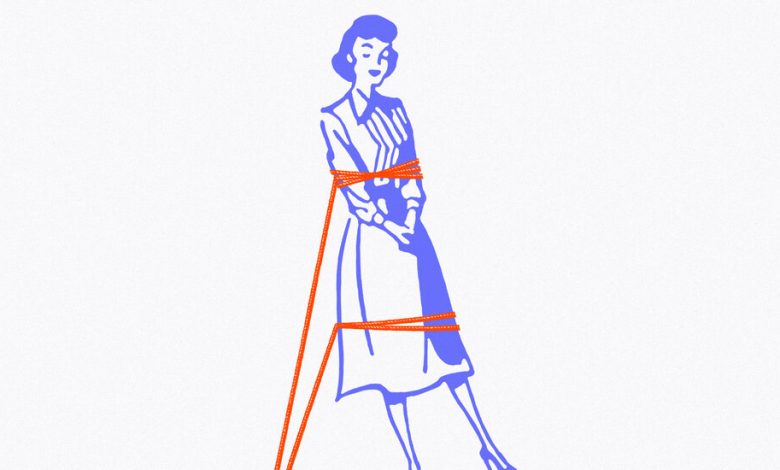

How Sexism Influenced Corporate Governance

Early in the 20th century, many owners of the iconic companies of the day were women. Before the 1929 stock market crash, female shareholders outnumbered male shareholders at AT&T, General Electric and the Pennsylvania Railroad (even though the men owned more shares).

But men had little respect for women’s ability to exercise their rights as owners to discipline company management. “You might as well ask the clouds in the air to propel the railroad locomotives,” William Cook, a widely read legal scholar, wrote in 1914.

This combination — the feminization of capital and men’s disdain for it — has had repercussions right up to today, according to an important article this year in Stanford Law Review by Sarah Haan, a professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law.

The lack of faith in women’s capabilities as shareholders contributed to the de-emphasizing of shareholders’ role in running companies, Haan argues. Laws and regulations, many of them from the New Deal, came to rely instead on the stock market to discipline companies, she writes. “The idea being that shareholders should exit companies if they’re uncomfortable with how they’re run: Discipline will occur through stock prices,” she told me in an interview.

That’s still kind of the way things work, Haan said. Executives who are paid in shares and stock options have an incentive to make the stock price go up. Corporate governance law emphasizes disclosure so shareholders have the information they need to decide whether to stay or sell. One problem: Market-based discipline doesn’t work for shareholders if they care about things other than the share price, such as fighting climate change.

Haan has a fresh perspective on the agency problem — the fact that shareholders own the company but their agents, the executives, effectively control it. Since so many shareholders were women, it was easy for (male) professors and executives to think of shareholders as passive and managers as active, she argues.

Alfred Sloan Jr., the head of General Motors, gave the game away in 1926 when he wrote of his fear that “diffusion of stock ownership must enfeeble the corporation by depriving it of virile interest in management upon the part of some one man or group of men to whom its success is a matter of personal and vital interest.” “Virile”? As Haan puts it, “Although Sloan did not mention women directly, his word choice suggests a gendered meaning.”

Sexism was blatant for decades. When in 1953 a female shareholder of Standard Oil of New Jersey asked why the company had no female directors, even though it reported having more women than men as shareholders, the chairman, Frank Abrams, said the company hadn’t found a woman “who can contribute to the problems we have to face.” He added, “I was going to say that first they would start with our interior decorating.”

The firmly held belief that women were content to be passive owners wasn’t even accurate. Haan recounts the activism of several women, including Wilma Soss, who challenged corporate policies that required female employees to retire at 55, versus 65 for men, and was forcibly removed from an annual meeting of IBM for persisting in trying to nominate a female director from the floor.

The 1950s marked the beginning of the end of the feminization of capital, according to Haan. More and more shares were held by institutions rather than individuals, and nearly all of those institutions were run by men. The institutions owned shares in many companies, relying more on diversification to protect themselves from bad management.

Haan argues that the conceptual division of companies between owners and managers is a relic of the early 20th century, one that mapped easily onto society’s two separate spheres occupied by women and men. In a forthcoming Southern California Law Review article, she argues that the division is really in three parts: management, a handful of very large asset managers and ordinary shareholders. Ordinary shareholders, including individual investors and pension funds, want the companies they own to beat the competition, while large asset managers that own all the companies in a sector would be happy to see less competition and higher profits.

Over the past decade or so, shareholders have gotten back some of their ability to control corporations directly. Most recently, a Securities and Exchange Commission “universal proxy” rulegives shareholders more say over how votes for directors are cast on their behalf. It took effect for elections in September. This “will bring shareholder voting closer to the political model for the first time in more than a century,” Haan writes in the forthcoming article. Maybe those “passive” shareholders aren’t so passive after all.

Number of the Week

4.5 percent

This is the top end of the target range for the federal funds rate that the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee is likely to choose at its two-day meeting ending on Wednesday, according to the median estimate of economists surveyed by FactSet. That would be an increase of half a percentage point from the current range of 3.75 percent to 4 percent, after four consecutive increases of three-quarters of a percentage point.

Quote of the Day

“From such crooked timber as humankind is made of, nothing entirely straight can be made.”

Immanuel Kant, “Idea for a Universal History With a Cosmopolitan Aim” (1784)

Have feedback? Send a note to [email protected].