Having a Hard Christmas? Jesus Did Too

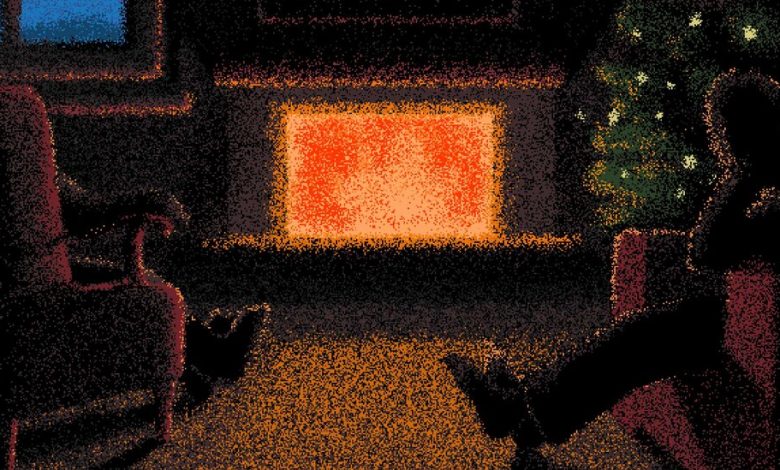

Among my most treasured memories is one Christmas Day when I was around 6 or 7 years old. Christmases in my childhood were fairly magical, with good food, lots of family, presents and fun. But that Christmas I was miserable. I lay in bed at my grandmother’s house, where we went for our Christmas feast, with a stomach bug, separated from the rest of the family so as not to spread my Yuletide germs. Alone and unable to eat, I listened sadly to the laughter and glee down the hall. Then my dad popped his head in the door. He brought me a ginger ale with a straw and sat at the end of the bed. He touched my forehead with the back of his hand to check my fever and joked with me gently and kindly.

My father was a complicated man who kept to himself at home and was often distant. We knew he loved us but he showed that more through mowing the lawn and filling up the gas tank rather than giving us hugs or telling us so. But that morning my father left the healthy people, the party and the food and came to spend time with me, just me. I don’t remember what gifts I got that year. I don’t remember what the decorations looked like or what food I missed out on, but I remember my father’s face, his voice, his hands, his smile.

This story comes back to me this time of year because the holidays are often a lonely time for many of us. And in some ways for all of us. No matter how many family members or friends we have, no matter how delicious the food on the table, in quiet moments, many of us still feel a lack, a pang in our hearts, the recurrent ache of longing. We long for peace that we cannot conjure on our own. We long for justice and truth to win out. We long for a joy that isn’t quite so elusive. We long for relationships that last. No matter one’s political affiliation, race, income or education level, we share a common human yearning for a wholeness and flourishing that we do not yet know on this convulsed and suffering planet.

It was my father’s presence that transformed that childhood Christmas, giving it meaning beyond just misery, making it burn bright in my memory. This little moment was a tiny, imperfect picture to me as a kid of what Christians celebrate this morning in nearly every language around the globe: God, like my father, entered our room. The radical claim that Christians make is that God has not remained aloof, transcendent, resplendent in majesty and glory, but became one of us, to be with us in the finitude, the bewilderment, the loneliness and longing of being human.

The analogy falls short. Christians believe that, unlike my father, Jesus was not simply a human messenger visiting us in our suffering. He was God-made flesh, “infinity dwindled to infancy,” as the 19th-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote. The Christmas story tells us that therefore Emmanuel — which means “God with us” in Hebrew — is in fact with us in the whole of our actual lives, in our celebration and merrymaking, in our mundane days, and in sickness, sorrows, doubts, failures and disappointments.

Christians believe that because God himself entered humanity, humanity is being transformed even as we speak. Because God took on a human body, all human bodies are holy and worthy of respect. Because God worked, sweating under our sun with difficulty and toil, all human labor can be hallowed. Because God had a human family and friends, our relationships too are eternal and sacred. If God became a human who spent most of his life in quotidian ways, then all of our lives, in all of their granularity, are transformed into the site of God’s surprising presence.

Yet what astounds me most about the Christmas story is not merely the notion that God became a baby or that God got calluses and cavities, had fingernails and friends, and enjoyed good naps and good parties. Christians proclaim today that God actually took on or assumed our sickness, loneliness and misery. God knows the depths of human pain, not in theory but because he has felt it himself. From his earliest moments, Jesus would have been considered a nobody, a loser, another overlooked child born into poverty, an ethnic minority in a vast, oppressive and seemingly all-powerful empire. We have tamed the Christmas story with over-familiarity and sentimentality — little lambs and shepherds, tinsel and stockings — so we fail to notice the depth of pain, chaos and danger into which Jesus was born.

God identifies himself most with the hungry and the vulnerable, with those in chronic pain, with victims of violence, with the outcasts and the despised. In “The Message,” a poetic paraphrase of the scriptures, the pastor and theologian Eugene Peterson translates John 1 by saying, “The Word became flesh and blood and moved into the neighborhood.” When Jesus, the Word, “moved into the neighborhood,” it was not into a posh home in a cozy Christmas movie but instead into a place of hardship and sorrow.

The hope of Christmas is that God did not — and therefore will not — leave us alone. In the midst of our doubts and suffering comes a baby. This child, Christians claim, is God’s embodied response to all of our human aching. In his book “Unapologetic,” Francis Spufford writes that Christians “don’t have an argument that solves the problem of the cruel world, but we have a story.” This story is one of God moving into the neighborhood.

Christianity hasn’t answered all my questions. It has not made me perfectly happy. It has not satisfied my sense of longing. If anything, my (often feeble) attempts to live as a Christian have heightened it. But the Christian story tells me that my deepest longings are not just farce, that they point to something true and therefore should be listened to. This Christmas I long not just for love, but for eternal love. I long for a deeper purity and righteousness than I can muster by good behavior. I long for a justice more profound than Congress can ever deliver. I long for “peace on earth and good will toward men” that is more complete and all-encompassing than we’ve ever known. I long for meaning that is more lasting than I can create. I believe that this baby born in Bethlehem is the mystery our hearts keep chasing, the end of our all quests and the longing we cannot shake.

So, friends, I hope you know longing this Christmas, and even more so, I hope you know hope.

Merry Christmas!

Have feedback? Send a note to HarrisonWarren-newsletter@nytimes.com.

Tish Harrison Warren (@Tish_H_Warren) is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America and the author of “Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep.”