Frederick Swann, Master of the Pipe Organ, Is Dead at 91

Frederick Swann, who in churches on the East Coast and the West played some of the world’s grandest organs, performing classical and religious works on the complex instruments with sensitivity and technical skill, died on Nov. 13 at his home in Palm Desert, Calif. He was 91.

The cause was cancer, said Karen McFarlane Holtkamp, who was Mr. Swann’s secretary in the 1960s and ’70s and then his concert manager.

Mr. Swann was well known in New York as organist and music director at Riverside Church in Manhattan, where he began playing in the 1950s.

In 1982 he reached a much wider audience when he moved to the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, Calif., home base of the Rev. Robert H. Schuller, the television evangelist. There he appeared each week on “Hour of Power,” one of the most widely watched religious programs in the country, with a viewership in the millions.

Before retiring in 2001, he also served for three years as organist at the First Congregational Church of Los Angeles, which has one of the largest pipe organs in the world. He also played thousands of recitals all over the United States and beyond.

That was no easy feat. Large pipe organs require much more than just keyboard dexterity, and each one is different. The acoustics in each church or hall also vary.

“Fred was a genius at controlling and maximizing the potential of very large pipe organs,” the organist John Walker, who succeeded Mr. Swann as music director at Riverside, said in a phone interview. “Every organ is absolutely unique. They are custom-made works of art, and Fred was so uniquely skilled at uncovering the timbres in each instrument that he was regularly invited to give inaugural recitals” — that is, the first public performance on a new or rebuilt organ.

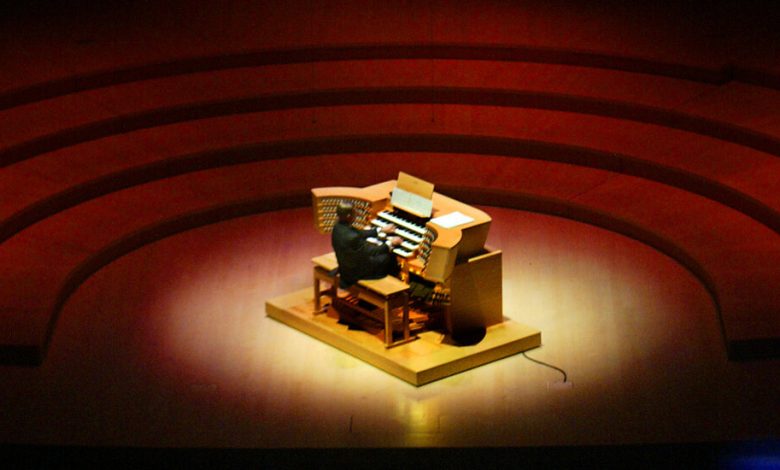

He filled that role in 2004 for the formidable organ at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, a 6,134-pipe instrument designed by Frank Gehry. His program that night included pieces by Bach, Mendelssohn and Josef Rheinberger.

“In all three,” Mark Swed wrote in a review in The Los Angeles Times, “the stirring deep pedal tones produced a sonic weight that seemed to anchor the entire building, while the upper diapason notes were clear and warm. The delicate echo effects in the slow movement of Mendelssohn’s sonata spoke magically, as if coming from the garden outdoors.”

Ms. Holtkamp noted that, at Riverside and other stops, Mr. Swann was choral director as well as organist; it was not uncommon to see him playing and conducting at the same time. His energy, she said, was boundless. She recalled one Sunday on which he played and directed the morning service at Riverside, played and conducted a portion of the Messiah at the church in the late afternoon, then headed to Lincoln Center to accompany the “Messiah Sing-In.”

“How Fred did so much so well in one day still amazes me,” she said by email. “I was totally worn out and I was only the page-turner!”

Mr. Walker said that Mr. Swann held four centuries’ worth of music in his head and generally played from memory. He played recitals of all kinds, sometimes as the featured attraction and sometimes accompanying a vocalist, and released numerous albums. Mr. Walker said his playing for religious services was particularly poignant.

“In playing a hymn,” he said, “he would be able to express the meaning of an individual word in such a poignant way that I would just immediately tear up.”

Frederick Lewis Swann was born on July 30, 1931, in Lewisburg, W.Va. His father, Theodore, was a Methodist minister, and his mother, Mary (Davis) Swann, was a homemaker.

Mr. Swann said he pounded on the family piano so much as a toddler that his parents locked it.

“Of course,” he told The Diapason, a publication about organs, in 2014, “any 3-year-old can figure out how to get into a piano if he really wants to, and I did.”

When he was 5 his parents arranged for him to take piano lessons from the organist at a nearby church. One day he arrived for his lesson and the teacher wasn’t waiting at the piano; he found her at the organ console, practicing.

“I was hypnotized watching things popping in and out,” he said. “Lights were flashing, her hands and feet were flying, and I thought, ‘Oh my, that looks like fun.’”

His legs weren’t yet long enough to reach the pedals, but eventually she began teaching him the organ — which was lucky, because when he was 10 the organist at his father’s church died, and there was no one else to step in but young Fred.

“It must have been simply awful,” he admitted, “but that’s how I got started at age 10, and I’ve just kept on.”

He earned a bachelor’s degree in music at Northwestern University in Illinois in 1952 and two years later received a master’s degree in sacred music at Union Theological Seminary in New York. He first played the Riverside organ while still a student. He also played at other Manhattan churches — sometimes, he said, he would provide music at four different churches on the same Sunday.

After two years in the Army, he began playing full time at Riverside in 1958. Eventually he became music director. A tribute on the Riverside website noted his role in helping to shape the sound of the church’s organ, a famed instrument.

“Although the organ was originally commissioned under the direction of Virgil Fox, Fred Swann was also on staff at the time of the installation of the organ in the mid-1950s,” it said. “In the succeeding years as director of music he oversaw a complete redesign of the organ console and supervised the organ’s expansion and tonal development. As such, he and those he worked with are responsible for the renowned instrument we hear today.”

Mr. Swann acknowledged that his departure from Riverside for the West Coast and the Schuller church in 1982 was viewed with disdain by some of his colleagues.

“They thought I had lost my mind because I had this beautiful Gothic cathedral, with a magnificent organ and a professional choir and really a lot of recognition as a church that set the standards in music,” he told The Los Angeles Times in 1998.

The Schuller services, in contrast, were known for their showiness and their hodgepodge of musical styles — a service might include a choral number and a country song. Mr. Swann elevated the musical content considerably, but he also broadened his own views.

“I feel like we’ve all benefited,” he told The Orange County Register of California in 1987. The challenge of adjusting to a new type of service appealed to him, he said. It also helped that the Crystal Cathedral had an impressive organ.

“It goes from barely audible to oh-my-gosh thunderous,” he told The Register in 2013.

Mr. Swann was married briefly to Mina Belle Packer in the 1950s. He is survived by his partner of 64 years, George Dickey.

Mr. Swann was active in the American Guild of Organists, serving as its president for six years beginning in 2002, and was a mentor to many younger players, including Mr. Walker.

“Most of what I know about how to play a church service I learned from standing next to Fred,” Mr. Walker said.

He was also known for his sense of humor, which was often on display in his chats with recital audiences. One time, Mr. Walker said, while giving the inaugural performance on an organ in Dallas, he was vexed by a “cipher” — a pipe that, because of a malfunction, refused to stop playing.

“New organs are just like new babies,” he explained to the audience. “They behave just fine until you take them out in public.”