Don Lewis, Unsung Pioneer of Electronic Music, Dies at 81

It was 1974, and Don Lewis was getting tired of hauling around so many keyboards. One day he would be in a studio in Los Angeles, working alongside Quincy Jones. A week later, he might be on tour as a member of the Beach Boys’ backup band. Or he might be performing his own gigs, shuffling up and down the West Coast with an ever-growing assortment of keyboards and other equipment.

He could have just taken his trusty Hammond Concorde organ, itself not a small item. But Mr. Lewis was an aural explorer, constantly on the hunt for new sounds. If he found a keyboard with a particular tone to it, he had to add it to his collection. He was a one-man band; he aspired to be a one-man orchestra.

His problem was about more than sheer weight. Each instrument had to be controlled separately, and there was no industry standard for integrating them. An electrical engineer by training, he decided to strip them down for parts and build something new.

It took him three years of designing and fund-raising, but in 1977 he finalized the Live Electronic Orchestra, commonly known as the LEO.

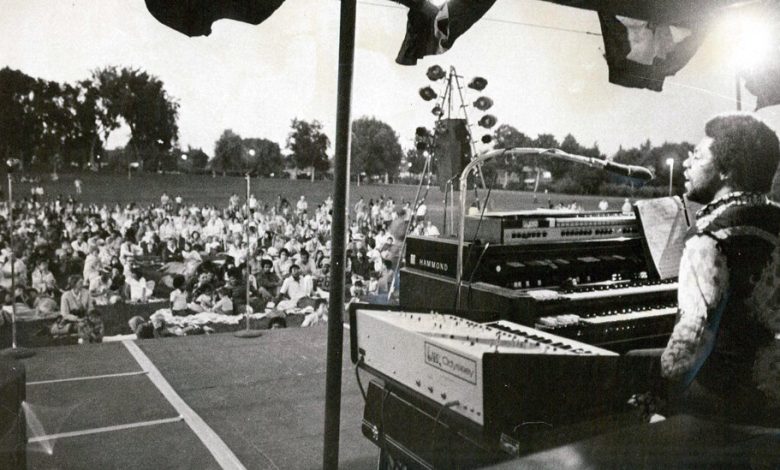

This musical Frankenstein’s monster brought together pieces from three keyboards, a slew of synthesizers, control panels and a drum machine into a set of plexiglass modules. Mr. Lewis sat in the middle, like a musical air traffic controller. His design allowed him not only to choose the sounds he wanted, but also to mix them in real time.

Mr. Lewis, 81, died on Nov. 6 at his home in Pleasanton, Calif. His wife, Julie Lewis, said the cause was cancer.

These days, people are used to the idea that they can produce virtually any sound they want on a laptop. That was far from the case in the 1970s, but Mr. Lewis found a way to create a symphony of sound at his fingertips.

The LEO cost more than $100,000, and he never made another. Still, it was a hit. He played six nights a week in a packed bar along Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Among his many fans was an engineer named Ikutaro Kakehashi, who was so inspired by Mr. Lewis’s invention that he went on to develop, with Dave Smith, the musical instrument digital interface, known as MIDI, the protocol that makes modern music production possible. (Mr. Smith died at 72 in June.)

A big part of Mr. Lewis’s success as a live musician was getting audiences to listen to him and not gawk at his keyboard rig. His technology was so clever, so seamless, that most people soon forgot about it entirely and allowed the music he created to sweep them away. He was an unsung pioneer of electronic music who paved the way for a billion beeps, boops and oonz-oonzes to come.

He wasn’t without his critics, who said that he was not a musician at all but a mere button-pusher. In the mid-1980s, members of the musicians’ union protested his performances, claiming that he would drive them out of business. He challenged their right to picket him before the National Labor Relations Board. He lost.

The prospect of having to cross a picket line just to do his job was too much. He stored the LEO in his garage and tried to put the whole experience behind him. Several years later, the government re-examined his case, and this time decided in his favor — and even gave him a settlement.

He didn’t bring back the LEO, though. He donated it to the Museum of Making Music in Carlsbad, Calif., where it sits on display today.

Donald Richard Lewis Jr. was born on March 26, 1941, in Dayton, Ohio. His father worked odd jobs, and his mother, Wanda (Peacock) Lewis, was a cosmetologist. They divorced when Don was very young, and he rarely saw his father again until decades later.

He grew up in a religious home, attending church at least once a week. Early on he became obsessed with the organ, and with the sounds that the church organist was able to draw out of it.

One night he had a dream that he had replaced the organist on the bench.

“I woke up and told my grandmother and grandfather, ‘I’ve got to learn the keyboard, because the feeling I had in that dream was something I hadn’t felt in my whole life,’” he recalled in the documentary “Don Lewis and the Live Electronic Orchestra,” scheduled to air on PBS in February.

He enrolled at the Tuskegee Institute in 1959 to study electrical engineering. He sang in the school chorus and even performed at a rally for the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

He stayed only two years. As tensions with the Soviet Union began to heat up, the Army was expanding the draft, and Black college students, unlike most white students, were often not exempt.

Mr. Lewis enlisted in the Air Force. He received training as a nuclear weapons specialist and served for nearly four years in Colorado and New Mexico.

After receiving an honorable discharge in 1965, he moved to Denver, where he was hired as an engineer for Honeywell, ran a church music program and worked part-time in a music store. Soon he was getting booked as a nightclub act, and eventually made enough to quit his day job.

Mr. Lewis spent the next several years on the road, often as a demonstration musician for Hammond, the organ company. He was already tweaking his instruments and equipment, looking for ways to eke out new sounds. He was also making his name as a studio engineer and musician, working with musicians like Mr. Jones and Marvin Hamlisch, especially after he settled in Los Angeles in the early 1970s.

Along with his wife, he is survived by his sister, Rita Bain Merrick; his sons, Marc, Paul and Donald; his daughters, Andrea Fear and Alicia Jackson; and five grandchildren.

After putting the LEO in storage, Mr. Lewis worked as a consulting engineer for companies like Yamaha and Roland. He was on the team that developed the sounds for Yamaha’s revolutionary DX7 — the instrument that defined 1980s synth pop — and the team behind Roland’s TR-808, perhaps the most popular drum machine ever made.

He taught at Stanford, Berkeley and San Jose State, and with his wife ran a program to bring music into elementary schools.

“I think music is more than entertainment,” Mr. Lewis said in the documentary. “I think it has a stronger and more meaningful purpose in our lives. And I think what we’re here to do as individuals is help people unlock and find those things that are dormant.”