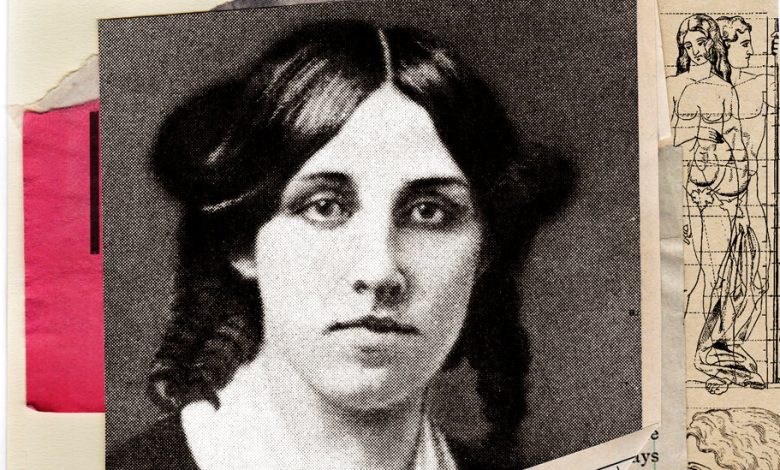

Did the Mother of Young Adult Literature Identify as a Man?

Louisa May Alcott balked when her editor asked her to write a book for girls. “Never liked girls or knew many,” she journaled, “except my sisters.”

Sisters were all it took. Alcott’s semi-autobiographical “Little Women,” which follows a family of four girls through the Civil War, made her a fortune upon publication in 1868. Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy have become immortal. They’ve captivated readers around the world in 50 translations and numerous adaptations. Louisa May Alcott may never have liked girls or known many, but her name is now synonymous with girlhood.

It’s a name that she didn’t use all that often in her personal life. To family and friends, she was Lou, Lu, or Louy. She wrote of herself as the “papa” or “father” of her young nephews. Her father, Bronson, once called Alcott his “only son.” In letters to close friend Alfie Whitman, Alcott called herself “a man of all work” and “a gentleman at large.”

All this leads me to wonder: Is Alcott best understood as a trans man?

I became curious about this question while conducting archival research for my next novel, a contemporary interpretation of “Little Women.” As I pored over letters, journals, and personal papers, I found evidence that Alcott thought of herself as more of a man than a woman — someone, as she wrote, in one letter to Whitman, “with a boy’s spirit under [her] ‘bib & tucker.’”

Alcott scholars agree that she felt a profound affinity with manhood. “I am certain that Alcott never fit a binary sex-gender model,” said Gregory Eiselein, a professor at Kansas State University and the current president of the Louisa May Alcott Society. In “Eden’s Outcasts,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Alcott, John Matteson wrote that Alcott believed “she should have been born a boy.” Jan Susina, a professor of children’s literature, concurred: “Alcott may have experienced what we today would consider gender dysphoria.”

Still, these scholars hesitate to use the word “transgender” to describe Alcott. “I’d like to be cautious about imposing our words and terms and understandings on a previous era,” says Dr. Eiselein. “The way folks from the 19th century thought about gender, sex, sexual identity, sexuality is different from some of the terms we might use.” Dr. Matteson shares Dr. Eiselein’s hesitation, and points to the particularities of Alcott’s social circle. “Emerson, Thoreau, and Louisa’s father, Bronson, all believed that human beings were fundamentally spirits who happened to be in a particular physical form,” he says, “but that the spirit should not be limited, that the spirit has an obligation to develop itself according to its own unique genius.” Alcott’s description of the divide between her female body and her male nature were certainly trans, suggests Dr. Matteson, but -cendentalist, perhaps, more than -gender.

Some fans of “Little Women” regard this entire line of inquiry as sexist. In April, I wrote a Twitter thread on Alcott’s gender identity. Tennis player Martina Navratilova, who has argued that trans women should not be allowed to compete in women’s sports, replied to me with consternation: “Do you have any idea how hard you would try to convince me I am trans if I were born 50 years later?” Her question seems to imply a concern that understanding a historical figure as a trans man might undermine gender nonconforming women and girls.

So is it inappropriate — anachronistic at best, misogynistic at worst — to describe Alcott as transgender?

I believe Alcott’s own statements give the lie to the notion that transgender identity is strictly a modern fad. “The historical record shows that people have felt in remarkably similar ways to contemporary transgender people,” says Susan Stryker, professor emerita of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona. What’s more, Alcott is a pertinent figure at a moment when trans books for youth are under attack from legislatures and school boards. What would it mean if the mother of young adult literature were actually the genre’s father?

The word transgender arrived in the English lexicon after Alcott’s lifetime. The German physician Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term “seelischer Transsexualismus” in 1923. The sexologist David Oliver Cauldwell translated this into “transsexual” in 1949, and the psychiatrist John F. Oliven proposed “transgender” as an alternative term in 1965. Alcott died in 1888, too early to use this vocabulary. Nonetheless, in an interview in the early 1880s, she declared, “I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body.” She may not have known the word “transgender,” but she certainly knew the feeling it describes.

What’s more, ‘transgender’ is precise; much alternative terminology is vague, even obfuscating. Consider the footnote that Dr. Matteson appends, in his “Annotated Little Women,” to a passage where Jo March, Alcott’s fictional avatar, examines her boots “in a gentlemanly manner.” This moment, he writes, is “the first firm indicator of Jo’s ambiguous gender identification.”

“‘Ambiguous gender identification’ is such a perfect illustration of how scholars see it, and they simply refuse to call it like it is,” said writerJames Frankie Thomas, a friend of mine, in an episode of Jo’s Boys, my “Little Women” podcast. “They will use euphemisms. They will water it down into something less real than it is. The word ‘gentlemanly’ — I’m sorry, ‘gentlemanly’ is not ambiguous.”

Dr. Matteson calls Mr. Thomas’s objection “a good point,” saying, “I do think that there is, among many scholars, a kind of inherent conservatism, an unwillingness to go out on too much of a limb.” In Alcott’s case, the limb isn’t even all that long: Is it any great sin to use a word coined in 1949 to describe a person who lived in 1888?

“History is about standing in our present, with all its contemporary issues and contemporary words, and looking to the past for insight,” said Judith Bennett, professor emerita of history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the University of Southern California. “Although some would object to a word like ‘trans’ being applied to the 19th century, the objection is spurious. We do it all the time with words like ‘feudalism’” — a term used in the 18th century, which no 10th-century serf would have used to describe their life.

No one would dispute that Joan of Arc was a resident of feudal France. Call her transgender, though, and charges of misogyny arise. In a recent essay for The Atlantic, the writer Helen Lewis criticized the play “I, Joan,” which portrays the saint as nonbinary. Ms. Lewis cited “British feminists” who excoriate “well-meaning revisionists” bent on deeming any gender nonconforming figure “too compelling to be a woman.” To “arbitrarily reallocate historical figures to new categories based on stereotypes,” argued Ms. Lewis, constitutes “misgendering.” So too with fictional characters, like Jo March.

Many readers today regard Jo as a tomboy who defies gendered stereotypes and blazes her own path in a world hostile to women. “It is hard to overstate what she meant to a small, plain girl called Jo, who had a hot temper and a burning ambition to be a writer,” said J.K. Rowling in 2012. I imagine that labeling Jo — or her author — as transgender would invite the ire of many a “British feminist.”

But then, how does Jo label herself? She opens the book by declaring, “I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy.” When stern older sister Meg asks Jo to behave, reminding her that she is “a young lady,” Jo answers, “I ain’t.” Jo’s delight in playing male parts onstage, her rejection of her feminine given name, her status as “son,” “brother,” and “man of the family” — all are original to Alcott’s 154-year-old text, borrowed from her own lived experiences. To insist that Alcott must be a woman, that she cannot be a man, is to replicate Meg’s cruelty.

Some fans argue that Alcott was not a trans man, but a lesbian. Alcott did speak of having “fallen in love in [her] life with so many pretty girls, and never once the least little bit with any man.”

However, there is no evidence that Alcott ever had a romantic or sexual relationship with a woman. Curiosity about the prospect is certainly evident in her writing: Jo pronounces, “I just wish I could marry Meg myself!” Alcott also explored male homosexuality, cross-dressing, and bisexuality in short stories like “My Mysterious Mademoiselle” and “Enigmas.” She was affectionate with many young men, particularly Alfie Whitman and Ladislas Wisniewski, who jointly inspired “Little Women’s” Laurie, but scholars disagree on whether she regarded them as romantic interests. “What I see is identification,” says Dr. Eiselein. “I think she wants to be them, or be like them.” Perhaps this is why Alcott insisted, in one letter to Whitman, that she was not “a prim spinster,” but “one of ‘our fellows.’”

Dr. Stryker, the University of Arizona scholar, argues it is possible to recognize the plain fact of Alcott’s identification with manhood without minimizing the impact of “Little Women”on women’s lives and literature. “We can all recognize Lou Alcott in many different ways,” said Dr. Stryker. “We don’t have to turn it into a pissing contest or a turf war.”

Alcott is neither the first historical figure to inspire a debate around identity, nor the most recent. Was Einstein autistic, or does the mere suggestion further stigmatize autism? What color was Cleopatra’s skin, and what does the answer mean for modern women of color? Was Ernest Hemingway a raging misogynist, or merely an egg? (That is, a transgender woman who never “hatched,” owing to the strictures of masculinity.) Emotions in these arguments run high. At stake is nothing less than who gets to claim a hero.

In the absence of necromancy to really settle the question, we must base our understanding of Alcott’s identity on her writing. “I long to be a man,” she wrote, in one journal entry. “I was born with a boy’s nature,” she added, in that letter to Whitman, and “a boy’s spirit” and “a boy’s wrath.” As a child, she didn’t “care much for girls’ things.” As an adult, just a few years from death, she saw herself as “a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body.” Why not take Lou at his word?

Peyton Thomas is the author of the novel Both Sides Nowand the host of Jo’s Boys: A Little Women Podcast.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.