Did the C.I.A. Kill Patrice Lumumba?

THE LUMUMBA PLOT: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination, by Stuart A. Reid

The man with the Bronx accent, by one account, announced himself on the telephone as “Sid from Paris.” It was late in September 1960, and Larry Devlin, the Central Intelligence Agency’s station chief in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, had been expecting this call. The men arranged a time and a place to meet, and then, adhering to counter-surveillance protocol, met an hour earlier than planned.

“Sid” was Sidney Gottlieb, an agency scientist who later became famous for his involvement in MKUltra, the C.I.A. mind-control program that involved dosing unsuspecting victims with huge amounts of LSD. He had been sent to Congo’s capital of Léopoldville — now called Kinshasa — with vials of poison.

Congo had been freed from its Belgian colonial yoke only three months earlier, and it had almost immediately descended into chaos as the army rebelled; the Belgians — unwilling to let go — dropped paratroopers; and various ethnic groups sought their own sovereignty. Worse for Devlin and the C.I.A., the country’s highly charismatic prime minister, Patrice Émery Lumumba, appeared to be lurching into the Soviet orbit. The poison Gottlieb carried with him was intended to kill Lumumba and stop Congo from falling into Moscow’s grip. When Devlin learned of this scheme, he was shocked. He asked who had authorized it. He would later recall that Gottlieb replied, simply, “President Eisenhower.”

The buildup to this plan and its denouement animates Stuart A. Reid’s “The Lumumba Plot,” a fascinating new book on Lumumba and the aftermath of the military coup that ended his government. Today, Congo is once again a focus of international interest because of its rich deposits of cobalt, copper and tantalum, metals that are used in electronics and batteries. Reid, an executive editor at Foreign Affairs, has arrived with a carefully researched book that warns us about what is lost when tensions between great powers play out in the developing world.

Ironically, the Soviets were not particularly helpful to Lumumba. Reid concludes that Russian support for the prime minister was lukewarm because even Soviet leadership thought “it more natural for the Congo to side with the United States.” Lumumba had tried to reach out to the Eisenhower administration early on, but Washington rejected his advances. In 1960, when the Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev heard that the United States would not provide aid to Lumumba’s government, he asked, “Are the Americans that stupid?”

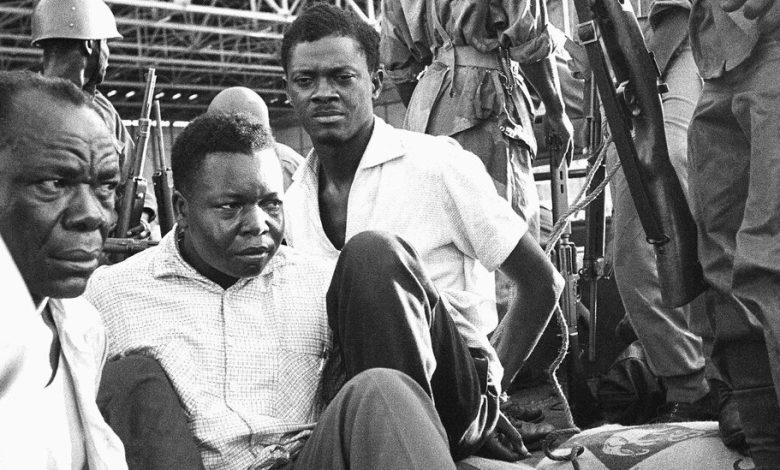

Now largely forgotten, the trouble surrounding Lumumba at the beginning of the 1960s grabbed headlines and stoked protests around the world. His administration lasted only 10 weeks. After his ouster, the military junta that seized control of Congo put Lumumba under house arrest. Four months later he was dead.

During the years of secessionist violence that followed Congo’s independence, some 100,000 people were killed. In December 1960, while Lumumba was imprisoned, at least 200 Congolese refugees fleeing the post-coup chaos starved to death each day. As Congo fragmented, the Pentagon drew up plans to restore stability that would have required an army of 80,000 troops and more transport planes than the U.S. then had. (The Kennedy administration used this scheme as a pretext to order more military aircraft.) U.N. officials worried that superpower competition in Congo could drag the United States and the Soviet Union into a nuclear conflict. The tumult dampened the sense of global optimism that attended decolonization across Africa.

Despite its subtitle, the book does not focus as much on the C.I.A. in Congo as on the concerns of diplomats in the United Nations and a bouquet of plots in Léopoldville. The international panic over the havoc in Congo, Reid writes, helped transform the Cold War “into a truly global struggle.”

Reid develops his main characters beautifully, especially Lumumba, who passes “like a meteor” — to borrow the lovely phrase of his daughter Juliana — through its pages. “He improvised rather than planned,” Reid explains. “Sometimes, Lumumba’s approach would pay off, allowing him to rise high and fast. Other times, he flew too close to the sun.”

From his early days in the backwater cotton town of Onalua in the 1930s and ’40s to his ascendance within the anticolonial Congolese National Movement party, Lumumba’s rise through adversity is nothing short of inspirational. But Reid also notes the stains on Lumumba’s record, especially the 1960 massacre at Bakwanga, an ethnic cleansing during which Lumumba’s men “raped, bayoneted or shot” thousands of people, one of the first in a long history of Congo’s post-independence mass killings.

Reid, however, broadly accepts Lumumba’s insistence that Congo stay together as the Belgians had fashioned it. Animosity engendered by this slapdash colonial paste job still fuels conflict and paranoia: While reporting on purported connections between separatists and mining in southern Congo last year, I was detained for six days by the secret police and deported.

What of the “plot” advertised in the book’s title? Reid is not the first biographer to point the finger at Dwight Eisenhower, but he comes bearing fresh evidence: At the Eisenhower Presidential Library, Reid tracked down the only written record of an order at an August 1960 National Security Council meeting with the president, during which a State Department official wrote a “bold X” next to Lumumba’s name.“Having just become the first-ever U.S. president to order the assassination of a foreign leader,” Reid writes of Eisenhower, “he headed to the whites-only Burning Tree Club in Bethesda, Md., to play 18 holes of golf.”

Lumumba is re-elevated by the end of Reid’s book, mainly through the sea of indignities he suffered as a captive. Particularly disturbing is an episode from late 1960. His wife gave birth prematurely and his daughter’s coffin was lost when neither of her parents was allowed to accompany it to its burial.

In 1961, Eisenhower’s fantasies of the Congolese leader’s death — he once said he hoped that “Lumumba would fall into a river full of crocodiles” — were fulfilled. Lumumba was captured after an escape attempt and shipped to Katanga, where a secessionists’ firing squad, supported by ex-colonial Belgians, executed him. Reid shows how the C.I.A. station chief in Katanga rejoiced when he learned of Lumumba’s arrival (“If we had known he was coming we would have baked a snake”)but doesn’t ultimately prove that the C.I.A. killed him.

The C.I.A. has long denied blame for the murder of Lumumba, but I still wondered why Reid doesn’t explore a curious story that surfaced in 1978, in a book called “In Search of Enemies,” by John Stockwell. Stockwell, a C.I.A. officer turned whistle-blower, reported that an agency officer in Katanga had told him about “driving about town after curfew with Patrice Lumumba’s body in the trunk of his car, trying to decide what to do with it,”and that, in the lead-up to his death, Lumumba was beaten, “apparently by men who were loyal to men who had agency cryptonyms and received agency salaries.”

Still, Reid argues convincingly that by ordering the assassination of Lumumba, the Eisenhower administration crossed a moral line that set a new low in the Cold War. Sid’s poison was never used — Reid says Devlin buried it beside the Congo River after Lumumba was imprisoned — but it might as well have been. Devlin paid protesters to undermine the prime minister; made the first of a long series of bribes to Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, the coup leader and colonel who would become Congo’s strongman; and delayed reporting Lumumba’s final abduction to the C.I.A. On this last point, Reid is definitive: Devlin’s “lack of protest could only have been interpreted as a green light. This silence sealed Lumumba’s fate.”

THE LUMUMBA PLOT: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination | By Stuart A. Reid | Knopf | 624 pp. | $35