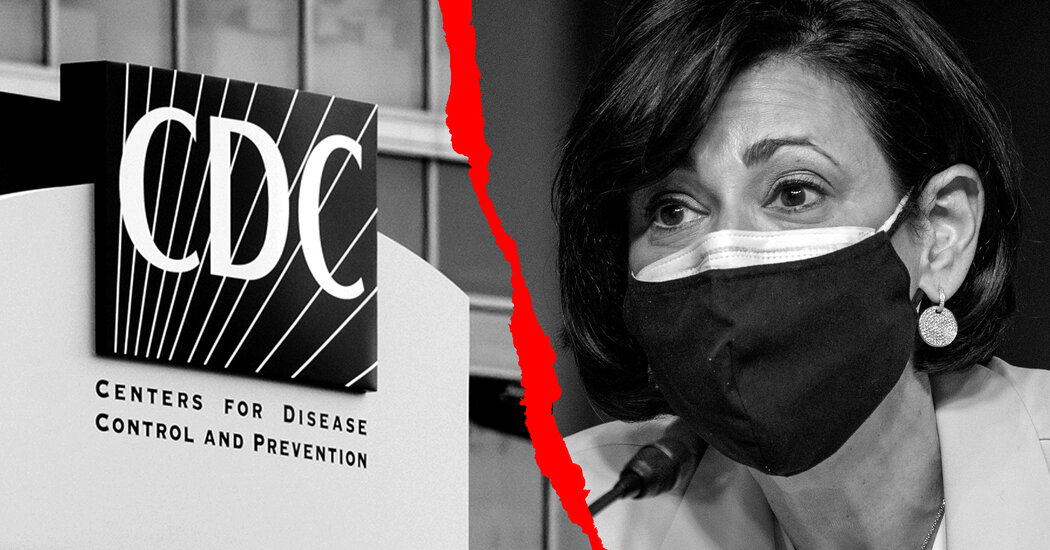

Can the C.D.C. Save Itself?

This article is part of the Debatable newsletter. You can sign up here to receive it on Wednesdays.

Last week, Dr. Rochelle P. Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, announced that the agency would be reorganized in light of a damning internal review of its widely criticized response to the coronavirus.

“For 75 years, C.D.C. and public health have been preparing for Covid-19, and in our big moment, our performance did not reliably meet expectations,” Walensky said. “To be frank, we are responsible for some pretty dramatic, pretty public mistakes, from testing to data to communications.”

The failure more than two years later to contain monkeypox — a much less contagious virus that was discovered decades ago and for which a vaccine already exists — seems only to underscore Walensky’s conclusions. “Although the U.S. might have once seemed like one of the nations best equipped to stop and prevent outbreaks,” Katharine J. Wu wrote in The Atlantic last month, “it is, in actuality, one of the best at squandering its potential instead.”

How can the C.D.C. regain the trust it lost during these past few years and ensure the country is better prepared for the next epidemic? Here’s what people are saying.

Getting eyes on the virus

One of the C.D.C.’s earliest blunders during the coronavirus pandemic was its distribution of test kits that turned out to be faulty. And because the Food and Drug Administration initially refused to allow laboratories to develop or use their own, “The void created by the C.D.C.’s faulty tests made it impossible for public-health authorities to get an accurate picture of how far and how fast the disease was spreading,” Robert P. Baird reported for The New Yorker in 2020. Monkeypox testing was much sooner to arrive, but it still didn’t ramp up quickly enough, as Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, argued in The Times.

Expediting the rollout of widespread testing in the future will require improving the accessibility and ease of testing where patients normally seek care, which is not something the C.D.C. typically concerns itself with, Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health, told me.

Unlike soon after the coronavirus was detected in the United States, the C.D.C. actually did have the capacity to run enough tests in the early weeks of the monkeypox outbreak before commercial labs were authorized to perform them in late June, she said. But health care providers were having an exceedingly difficult time ordering tests through the C.D.C.’s lab network.

“If the most motivated health care centers in the world can’t navigate the system, the urgent care doctor that someone is going to see about this weird rash they have is definitely not going to be able to,” she told me. “Hearing from the clinicians who were complaining about it should have prompted the C.D.C. to say, ‘You know what, we have to be more responsive.’”

Cleaning up America’s data mess

If the United States’ approach to testing for novel and uncommon pathogens suffers from too much centralization, its approach to collecting and reporting test and case data has suffered from the opposite problem. As Miranda Dixon-Luinenburg wrote in Vox, the country’s health care system is deeply fragmented among states, local health departments, hospitals, clinics and laboratories, with no single organization in charge of facilitating communication or standardizing data formats. As a result, the government had to rely on data from Israel and Britain, both of which have national health care systems, to shape its coronavirus vaccination strategy.

Similar issues have hindered the U.S. response to monkeypox, which was first reported in the country in mid-May. But through August, the C.D.C. possessed detailed demographic information on less than half of all reported cases, and its demographic data on who is receiving the vaccine is likewise incomplete.

C.D.C. officials often cite the fact that they depend on local and state governments to report data and cannot, in most cases, compel them to do so. That’s true, Gottlieb said, but the agency could still do a better job of synthesizing the information it does have. And Nuzzo suggested that the C.D.C. could also play a more active role in gathering data by working with states and local health care providers to conduct targeted, well-designed surveillance to monitor how a given virus is spreading and sickening people, as it does with the flu.

Fixing the C.D.C.’s messaging problem

As Walensky admitted last week, the C.D.C. has not done the best job of communicating its findings and recommendations to the public, calling its coronavirus guidance “confusing and overwhelming.”

Part of that confusion, my colleague German Lopez recently argued, owes to the tendency of public health officials to speak around the truth in a bid to manage the public’s reaction to it. In the early weeks of the coronavirus’s spread, for example, officials discouraged the use of masks — not because they were convinced masks didn’t work, but because they feared public demand would cause a shortage of masks for health care workers. And during the monkeypox outbreak, some officials have been reluctant to acknowledge that the virus is mostly infecting men who have sex with men to avoid stigmatizing that population — but in the process are failing to give an accurate picture of how the virus is spreading and who, at least for now, is most at risk.

While Walensky’s acknowledgment of the C.D.C.’s messaging missteps is encouraging, it would be a mistake to think of them “simply as a question of style or choice of words,” the Times columnist Zeynep Tufekci told me. In her view, some of the C.D.C.’s communication troubles are directly tied to weaknesses in its ability to gather data and nimbly but rigorously synthesize it, which hamper the agency’s pursuit of honoring what it says are some of the most important principles of crisis communication: “Be first, be right, be credible.”

The C.D.C. also doesn’t do enough to incorporate high-quality data from abroad.As early as the end of May of 2021, for example, there were signs about the danger of the Delta variant, but the C.D.C. failed to respond appropriately until it produced its own study in July, which ended up being inferior to studies other countries had already worked up.

“There is no way to fix all this with attention just to communication,” Tufekci told me. “Weak data and claims inevitably damage credibility no matter how well crafted the press release might be.”

Regaining independence

During the coronavirus pandemic’s first year, public health experts — including former employees of the C.D.C. — expressed alarm at the Trump administration’s interference with the agency’s work: Government scientists were ignored and silenced, their reports and guidance altered, in service of the White House’s desire to downplay the risk of the virus and project a sense of normalcy.

President Biden vowed that he would “listen to the science,” and he has been much more deferential to public health experts. But he has also on occasion gotten ahead of scientific consensus — such as when he championed booster shots for all Americans shortly after a C.D.C. panel voted against the idea — in ways that could be interpreted as a form of political pressure. (Biden’s position was later vindicated, raising questions about the C.D.C.’s judgment.)

In the view of the Washington Post editorial board, the C.D.C. still needs more distance from the president: “The pandemic response remains under a White House coordinator; shortly before monkeypox became an emergency, it, too, was put under a White House overseer. The goal should be for experts at retooled public health agencies to fight health crises, not politicians in the White House.”

To increase the C.D.C.’s independence, Congress could move the C.D.C. outside its parent agency, the Department of Health and Human services, as James Hamblin, a journalist and a lecturer at the Yale School of Public Health, suggested in The Times in March. “Within that arrangement,” he added, “it may also be possible to limit the influence of any given president over public health, for example by requiring congressional approval of C.D.C. directors, possibly for a term that does not coincide with presidential terms.”

Beyond the C.D.C.

Many of the failures of the U.S. responses to the coronavirus and monkeypox are not solely the fault of a single agency, but of a national public health system that has been hollowed out by disinvestment. As my colleague Jeneen Interlandi wrote in 2020, health care spending rose by more than 50 percent in the past decade, while the budgets of local health departments shrank by as much as 24 percent and the C.D.C.’s budget remained flat. When a public health crisis does occur, the country responds with only temporary funding measures.

“We ignore the public health sector unless there’s a major catastrophe,” Scott Becker, the head of the Association of Public Health Laboratories, told Interlandi. “Then we throw a pile of money at the problem. Then we rescind that money as soon as the crisis abates.”

This approach has some obvious drawbacks. Years before the current monkeypox outbreak, top health officials knew that the country’s supply of the Jynneos vaccine was highly insufficient, as the Strategic National Stockpile was never given enough money to purchase the millions of doses that experts thought were necessary. And while the coronavirus pandemic isn’t over, additional funding for it is stalled in Congress, so the federal government is having to ration what resources it has left.

How much would a modern, national public health system cost? One estimate, from a nonpartisan commission financed by the Commonwealth Fund, is $8 billion in additional funding per year. Most of that money would go toward alleviating local worker shortages, Leana Wen reported in The Washington Post, while the rest would pay for a data system connecting public health agencies and hospitals.

“The C.D.C., no matter its importance, is just one element in America’s public health system, and any comprehensive analysis of shortcomings during the Covid-19 pandemic must also include other key players at the federal, state and local level — both public and private,” wrote Ronald Valdiserri, a former senior C.D.C. official, in Health Affairs. “In other words, modernizing C.D.C. systems without a concomitant investment in state, local and tribal departments of health, and their attendant workforces, will fail to deliver an improved response to the nation’s next pandemic.”

Do you have a point of view we missed? Email us at [email protected]. Please note your name, age and location in your response, which may be included in the next newsletter.

READ MORE

“Covid Proved That the C.D.C. Is Broken. Michael Lewis Has Ideas for How to Fix It.” [The New York Times]

“Inside America’s Covid-reporting breakdown” [Politico]

“Inside America’s monkeypox crisis — and the mistakes that made it worse” [The Washington Post]

“Monkeypox is a new global threat. African scientists know what the world is up against.” [Science]