California Bill Could Restrict the Use of Rap Lyrics in Court

A California bill that would restrict the use of rap lyrics and other creative works as evidence in criminal proceedings has unanimously passed both the State Senate and Assembly, and could soon be signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

The bill, introduced in February by Assemblyman Reginald Jones-Sawyer, a Democrat who represents South Los Angeles, comes amid national attention on the practice following the indictment of the Atlanta rappers Young Thug and Gunna on gang-related charges. Prosecutors have drawn on the men’s lyrics in making their case.

The California measure, however, would apply more broadly to any creative works, including other types of music, poetry, film, dance, performance art, visual art and novels.

“What you write could ultimately be used against you, and that could inhibit creative expression,” Mr. Jones-Sawyer said Wednesday in an interview. He noted that the bill ultimately boiled down to a question of First Amendment rights.

“This is America,” he said. “You should be able to have that creativity.”

Mr. Newsom has until Sep. 30 to sign the bill into law. If he neither signs nor vetoes the bill by that date, the measure would automatically become law. The law would then go into effect on Jan. 1, 2023, Mr. Jones-Sawyer said.

When asked whether Mr. Newsom planned to sign the bill, his office said that it could not comment on pending legislation. “As will all measures that reach the governor’s desk, it will be evaluated on its merits,” it said.

Though the bill’s genesis is in preventing rap stars’ lyrics from being weaponized against them, the measure loosely defines “creative expression” to include “forms, sounds, words, movements, or symbols.”

It would require a court to evaluate whether such works can be included as evidence by weighing their “probative value” in the case against the “substantial danger of undue prejudice” that might result from including them. The court should consider the possibility that such works could be treated as “evidence of the defendant’s propensity for violence or criminal disposition, as well as the possibility that the evidence will inject racial bias into the proceedings,” the bill says.

“People were going to jail merely because of their appearance,” Mr. Jones-Sawyer said. “We weren’t trying to get people off the hook. We’re just making sure that biases, especially racial biases toward African Americans, weren’t used against them in a court of law.”

The bill would require that decisions about the evidence be made pretrial, out of the presence of a jury.

For decades, prosecutors have used rappers’ lyrics against them even as their music has become mainstream, with critics and fans arguing that the artists should be given the same freedom to explore violence in their work as were musicians like Johnny Cash (did he really shoot a man in Reno just to watch him die?) or authors like Bret Easton Ellis, who wrote “American Psycho.”

In other cases, though lyrics were not used as evidence, they were discussed in front of the jury, which “poisoned the well” by allowing bias to enter the court, according to Mr. Jones-Sawyer’s office. It also noted that while country music has a subgenre known as the “murder ballad,” it is only the lyrics of rap artists that have been singled out.

Charis E. Kubrin, a professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California, Irvine, who has extensively researched the use of rap lyrics in criminal proceedings, said that the way prosecutors have used defendant-authored lyrics in court was unique to rap.

The practice, she said, essentially treated the lyrics as “nothing more than autobiographical accounts — denying rap the status of art.” The California bill is significant, Dr. Kubrin said, because it would require judges to consider whether the lyrics would inject racial bias into proceedings. “This is bigger than rap,” she said.

Among the first notable times the tactic was used was against the rapper Snoop Dogg at his 1996 murder trial, when prosecutors cited lyrics from “Murder Was the Case.” The rapper, whose real name is Calvin Broadus, was acquitted.

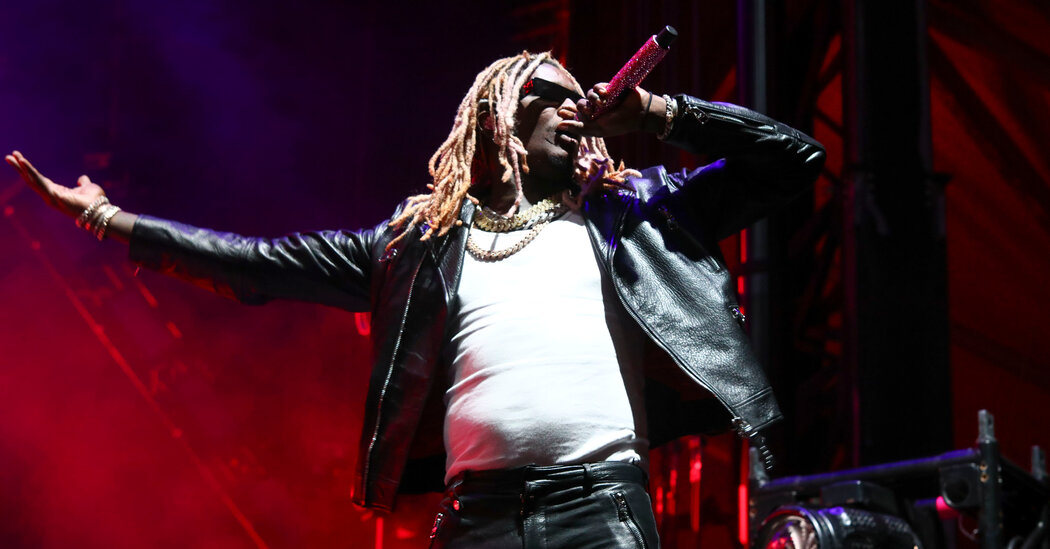

Most recently, the charges against Young Thug and Gunna have called national attention to the tactic. Both men, who have said they are innocent, were identified as members of a criminal street gang, some of whom were charged with violent crimes including murder and attempted armed robbery.

Young Thug, whose real name is Jeffery Williams, co-wrote the Grammy-winning “This is America” with Childish Gambino and is one of the most influential artists to emerge from Atlanta’s hip-hop scene.

In November, two New York lawmakers introduced a similar bill that would prevent lyrics from being used as evidence in criminal cases unless there was a “factual nexus between the creative expression and the facts of the case.” It passed the Senate in May.

In July, U.S. Representatives Hank Johnson of Georgia and Jamaal Bowman of New York, both Democrats, introduced federal legislation, the Restoring Artistic Protection Act, which they said would protect artists from “the wrongful use of their lyrics against them.”

The California bill is supported by several other music organizations and activist groups, including the Black Music Action Coalition California, the Public Defenders Association and Smart Justice California, which advocates criminal justice reform.

In a statement of support from June, the Black Music Action Coalition, an advocacy organization that battles systemic racism in the music business, said that prosecutors almost exclusively weaponized rappers’ lyrics against men of color.

“Creative expression should not be used as evidence of bad character,” the organization said, maintaining that the claim that themes expressed in art were an indication of the likelihood that a person was violent or dishonest was “simply false.”

Harvey Mason Jr., the chief executive of the Recording Academy, which runs the Grammy Awards, said that the bill was intended to protect not only rappers, but also artists across all genres of music, and other forms of creativity.

“It’s bigger than any one individual case,” Mr. Mason said. “In no way, at no time, do I feel that someone’s art should be used against them.”