A Raucous New Festival, With a Friends and Family Vibe

For obsessive dance-goers, it’s been a while since January in New York felt like January in New York. Remember American Realness at Abrons Arts Center? Coil at P.S. 122? Even before the days of Covid-19, those bustling experimental festivals of the 2010s — which coincided with the annual Association of Performing Arts Professionals conference, when lots of curators are in town — had quietly faded away, along with the flood of adventurous work they brought to theaters each winter.

Picking up the torch with an even more anti-establishment spirit is a new interdisciplinary festival, Out-FRONT! Organized by members of the grass-roots arts collective Pioneers Go East, which spotlights the work of queer and feminist artists, the inaugural edition opened last week at the L.G.B.T. Community Center in Greenwich Village.

That location was itself a smart choice on the part of the curators — Gian Marco Riccardo Lo Forte, Hilary Brown-Istrefi and Philip Treviño — positioning art in a context of community-building and care. At the performances I attended, the atmosphere often felt more like a lively and laid-back gathering of friends and family than the kind of networking event so common on the January festival circuit.

The line between performing for an audience and just hanging out was most porous, and gorgeously so, in Jasmine Hearn’s grounding and incandescent “Salt and Spirit,” on Wednesday. “We build this moment together,” Hearn (who uses they/them pronouns) has said of their highly collaborative practice, which encompasses dance, poetry, song and the lyricism of fabric. (This work features garments designed by Athena Kokoronis and Malcolm-x Betts.) As Hearn remarked when it was over, what had just happened would never happen quite this way again.

Of course, this is true of all live performances. But Hearn’s partially improvised creations have a delicacy and immediacy that somehow make you more aware of, and enchanted by, their fleetingness. “Salt and Spirit” reaffirmed what I’ve often felt about Hearn, that where they go, I want to follow.

As the audience entered the event space, Hearn and fellow performers — Lily Gelfand, Dominica Greene, Kendra Portier, Charmaine Warren and Marya Wethers — were already in motion, playing around with dance ideas and greeting friends as they arrived. Hearn invited us to feel the rise and fall of our breath, to be “with your own time and your own tempo.” As we tuned into ours, the dancers settled into theirs.

The spirals, swells and dips of Hearn’s movement, on their own and in a lush duet with Portier, migrated between patches of shadow and light, vivid even in darkness. Greene and Warren, a few decades apart in age, discovered tender entanglements, Greene picking up and spinning Warren or walking on Warren’s feet, as Hearn intoned “it’s been so long since I found me.”

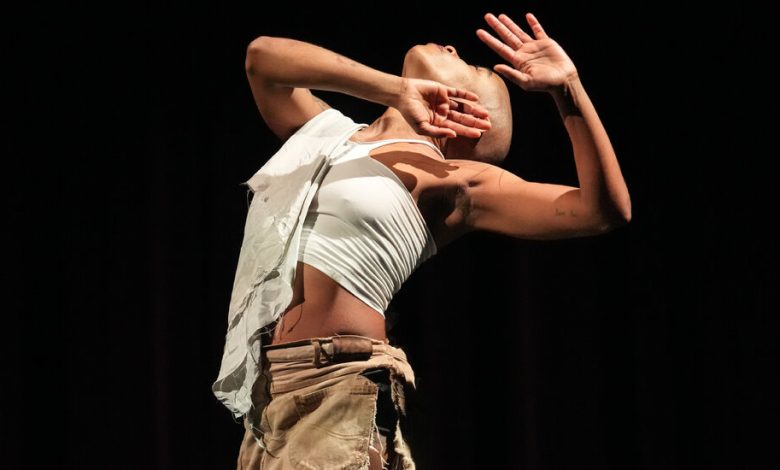

In waves of song and spoken word, sometimes punctured by a flinch or deliberate flat note, Hearn’s deep and deeply embodied voice mingled with Gelfand’s live cello, or made way for a sample of Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “My Journey to the Sky.” In a recent interview, Hearn described the work’s soundscape, which included contributions from Angie Pittman and Becky Selles, as “the house we get to run around in.” Clothing added to that sense of play: Portier’s black sequin dress over turtleneck and track pants, layered further with a hand-painted T-shirt by Betts; Hearn’s ripped, backward jeans paired at times with the wisp of an iridescent cape.

While “Salt and Spirit” had a way of gently holding and supporting its audience, other works in the festival held us in a state of high suspense. Arien Wilkerson, Chloe Newton and Kwami Winfield (of Wilkerson’s Philadelphia-based collective, Tnmot Aztro) offered the impressively unruly “835 Hours of Hope & Despair,” which set out to examine, according to a program note, “how conditional forces of pain for queer people of color are compounded by social economic conditions, manic institutions and flawed educational systems.”

At once scrappy and extravagant, “835 Hours” seemed to channel and transmute that pain, through frantic and funny dialogue, sweeping dance phrases, ambitious costume changes, commentary on academic texts — at one point, a copy of Hal Foster’s “The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture” landed at my feet — and ear-piercing noise, as the subdued trumpet and static of Winfield’s sound composition built to a blare. Offsetting the freedom and amplitude that Newton and Wilkerson found in their movement, eye-catching video avatars of the duo appeared behind them, in which they appeared more constrained, controlled. (Wilkerson and Jacob Weinberg are credited with tech and installation design.)

Embedded in Sunday’s raucous performance of “835 Hours,” I sensed a critique of even this most socially conscious festival. “That was long; they could’ve put that in the program,” Wilkerson said after the Indigenous land acknowledgment and “inclusivity and diversity acknowledgment” that preceded the show (and every show in the festival). In what I think was an improvised exchange, Newton and Wilkerson joked (or were they joking?) about calling the cops on curators. Assuming a statuesque pose that they called “the end of the patriarchy,” they urged us to take a photo so they could sell it and “get rich.” Live art, alas, doesn’t pay the bills.

A lighter but still tense mood hovered over Symara Johnson’s exhilarating “The Kitchen Sink Wrangler at the Midnight Rodeo” last Friday. Here, the tension arose from Johnson’s sly questioning of the audience — “What’s the difference between me and you?” she asked at one point, before clarifying, “It’s rhetorical!” — and from her intrepid interactions with a suite of plastic chairs, which she hoisted, dragged, tipped and balanced on. (In a post-show talk, she aptly described this activity as “beating up objects.”) This came after a stunningly strong opening: a hip-winding dance to Tems’s “Replay” that had the audience screaming, and that demonstrated, right off the bat, just how fearlessly Johnson can commit to a task.

Shifting into a more conversational gear, Johnson closed with highlights from her study of trick rope, which she’s taken up via YouTube in recent years. In addition to being fun to watch, these maneuvers extended the work’s underlying themes of truth versus fiction, of reality versus what lies beyond it.

“I really like to go to the edge,” Johnson said in an earlier monologue. In “Kitchen Sink,” she went there — and fully brought us with her.

Out-FRONT!

Through Thursday at the L.G.B.T. Center, Manhattan; pioneersgoeast.org.