A Journey to the Boot of Italy, With Murder, Romance and Ricotta

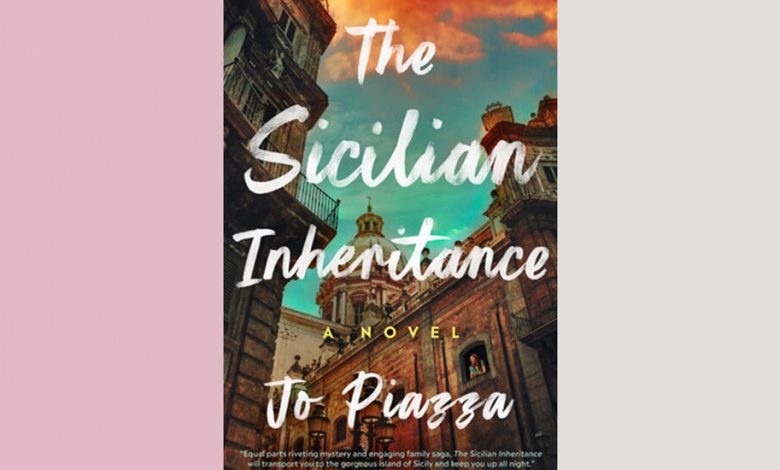

THE SICILIAN INHERITANCE, by Jo Piazza

I am a novelist and a reader — all I want in the world is hot coffee and time to read and write. Since I was a tween devouring “Flowers in the Attic” and the Rabbit Angstrom novels — who let me read Updike as a kid? — I have been drawn to flawed characters, complicated worlds and propulsive stories that overwhelm me with uncomfortable emotions.

So I opened Jo Piazza’s new novel, “The Sicilian Inheritance,” with anticipation. Piazza is a best-selling author and veteran reporter; her work runs the gamut between comic novels and nonfiction examinations of marriage and celebrity. With “The Sicilian Inheritance,” she boldly, if at times uneasily, combines romance, murder and history.

The story centers first on the Philadelphia chef and mother Sara, a trained butcher with a tattoo of a meat cleaver on her left forearm and a flying pig on her right. Although she is facing the end of her marriage and the bankruptcy of her restaurant, she’s also mouthy and ambitious, a character I adored from the moment she donned a bright red jumpsuit to attend her beloved Aunt Rosie’s “fun funeral” (personalized trivia, Dolly Parton karaoke) at a bar. “The jumpsuit was too tight and too low-cut,” Sara admits, “but I knew Aunt Rosie would have loved it.”

Afterward, Sara opens a letter containing Rosie’s “last wish from the great beyond,” in which she explains that she has booked a nonrefundable trip for her niece to visit her ancestral homeland, the fictional town of Caltabellessa, Sicily, so she can discover the truth about her namesake grandmother Serafina’s death and investigate a valuable property that may or may not belong to their family. “I’m sending you on an adventure, my love,” writes Rosie. “Don’t you dare waste it.”

Enter the book’s second first-person narrator, Serafina, a young girl in circa-1910s Italy who dreams of escape from “generations of women before me [who] had lived their entire lives circling the tip of the small mountain doing nothing but caring for babies and husbands.” But Serafina’s attempts to break free — by serving her townspeople as a doctor-healer of sorts, and allowing herself to love a man outside the bounds of matrimony — lead to her being labeled a “witch,” and possibly to her untimely death.

By Page 53, I put the book down, but not for long. I simply had to go online and search for flights to Italy. (I did the same while reading “Siracusa,” by Delia Ephron, another intoxicating tale set on the largest island in the Mediterranean.) Here, Sicily shimmers off the page, utterly enticing — azure waters for swimming, hunky Italian chefs, moments like this one that nearly made me drop a few thousand bucks I do not have on plane and ferry tickets: “The cheesemonger asked both of us to open our mouths and close our eyes before placing velvety ricotta directly onto our tongues.”