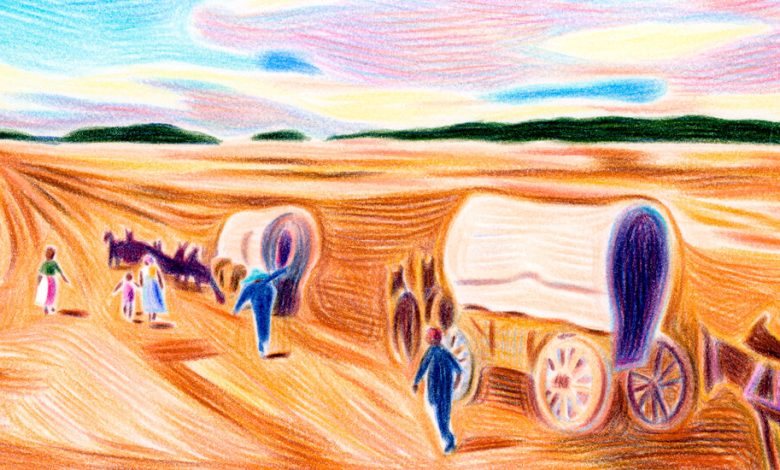

A Child’s-Eye View of One Black Family’s Covered-Wagon Journey

ONE BIG OPEN SKY, by Lesa Cline-Ransome

From a history book released in paperback in 1992, during my freshman year of college, I learned about the thousands of Black people who left the South in the late 19th century to move to the West, pursuing freedoms promised by the Homestead Act of 1862. The feminist Nell Irvin Painter’s “Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction,” originally published in 1977, was one of the first detailed studies of this mass movement by an African American historian.

There is a passage in Painter’s 1992 introduction that stands out as a disclaimer: “Unlike many other histories of Reconstruction, this book does not focus on Washington or the state capitals of the South. My central figures are not officeholders or men able to influence policy directly. (I say men because women, while they participated in the Exodus, were not voters during Reconstruction and do not appear as actors or speakers in the sources.)”

Lesa Cline-Ransome’s historical novel in verse, “One Big Open Sky,” is determined to fill in these archival silences. It tells the story of one Black family’s perilous covered-wagon journey from Mississippi to Nebraska through the voices of three resourceful and resilient female characters: the 11-year-old Lettie; her pregnant mother, Sylvia; and a young teacher, Philomena, whom they meet along the way.

Driving the wagon, and the decision to gamble everything on the chance of a better life (“We can’t live free/on someone else’s land/picking someone else’s crop!”), is Lettie’s father, Thomas. Her two younger brothers, Elijah and Silas, have had a hard time, as has her mother, adjusting to the idea of leaving the only community they’ve ever known: “Soon as Daddy finished talking/Elijah started fiddling/with his boot laces/ … When we coming back?/he asked Daddy/from moving I mean/I saw Momma’s eyes fill up/Ain’t no coming back once we leave ’lijah/Daddy told him/So why we leaving then?/Silas asked.”

Though it spans just nine months in 1879, Cline-Ransome’s lyrical tale reminds us that this often forgotten Black resettlement, which predated the Great Migration (the subject of her award-winning “Finding Langston” trilogy) by roughly three decades, was epic in its political ambitions and actual execution. The movement — in both senses of the word — is vividly captured by the book’s narrative flow.

“One Big Open Sky” mainly presents the alternating points of view of mother and daughter, until Philomena joins them. Their differences in age, anxieties and aspirations are so vast that their stories, even as they converge, remain distinct and enable us to understand the debates and desires that motivate them, as well as the Black male leaders galvanizing them and the white communities discriminating against them.