A Belarusian Writer Who Calls for Poems Made of Barbed Wire

MOTHERFIELD: Poems and Protest Diary, by Julia Cimafiejeva. Translated by Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib.

I type the town of Sperizh’e into Google Maps. All I see is decontextualized green, so I zoom out until my screen shows a location in southeast Belarus, no more than 50 kilometers from the Ukrainian border — far closer to Kyiv than Minsk. To the immediate left of Sperizh’e is the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve, an enclosed territory created in 1988 to cordon off the land most affected by fallout from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Sperizh’e is the hometown of the Belarusian poet Julia Cimafiejeva (born 1982), whose trenchant first collection in English, “Motherfield,” is now available. In one of the poems, “Rocking the Devil,” Cimafiejeva describes being a schoolgirl waiting for the bus the day after the explosion. As the acid raindrops begin to fall, she and her sister playfully stick their tongues out to collect them. The trees sway in the storm, she recalls, “the branches waving to us: ‘Farewell!’”

Tongues, Cimafiejeva wants us to understand, have been a matter of life or death in Belarus for as long as she can remember. In his efforts to appease Moscow, Belarus’s president, Aleksandr Lukashenko, has overseen a campaign to sideline the Belarusian language in favor of Russian. In recent years, publishers and booksellers who promote Belarusian literature have seen their licenses revoked and shops closed, as part of a broader crackdown on the country’s intelligentsia.

For a poetry collection from a Belarusian-language poet, “Motherfield” starts off unexpectedly — with prose written originally in English. The piece in question, “Protest Diary,” traces Cimafiejeva’s time in Minsk during the antigovernment protests (and their brutal repression) that swept the country in 2020. At an event with PEN Sweden in 2021, Cimafiejeva — who now lives in Austria — explained that she wrote it in another language to create distance for herself. She also could not write poetry; she was too glued to Facebook, to the testimonies pouring across her feed. Inspired by the experimental oral histories of Svetlana Alexievich, she wrote “Protest Diary” in an effort to capture this record of daily life. Fittingly, one of the protesters’ slogans was “Every Day,” a call for nonstop demonstrations.

Cimafiejeva describes walking to the polling station on Aug. 9, Election Day in Belarus. By the entrance “a teenage girl in a pseudo-folk costume with a wreath on her head” sings, in Russian, “about her love for the Motherland.” That same night, as the exit polls revealed a landslide victory for Lukashenko, protesters began to gather in cities and towns across Belarus. The internet had been shut off, but Cimafiejeva was able to access her Telegram app “through multiple proxy servers.” On her phone, she read reports of “military vehicles driving into peaceful gatherings, stun grenades thrown at the unarmed, shooting at the peaceful protesters who disagree with the results of the rigged election.” It is said, she writes, that the police were distributing Covid-infected prisoners across cells to spread the virus. She is scrolling her feed when a text message arrives from her brother: “Taken. Me.”

The internet is the dominant theme of “Protest Diary,” though it comes, as in life, in and out. Between poetry readings and meals, Cimafiejeva is always looking at her screen. “I feel nailed down to the kitchen stool,” she writes. During the 2020 protests in Belarus internet access was wielded like a weapon: the government shutting it down on one side, the people finding a way to bring it back to life on the other. The Telegram channel Nexta became a key source of information for protesters and was thus labeled “extremist” by the government (in 2021, subscribing to it carried a seven-year prison sentence). “Protest Diary” sometimes reads like a manual on digital disobedience. On Oct. 1, before a demonstration, Cimafiejeva writes, “It’s important to clear all the history off your cellphone.” Elsewhere, after her brother’s arrest, she mentions a Telegram channel listing detainees. The whole thing makes American discourse on the “internet novel” and the question of how to represent our addled Twitter brains feel embarrassingly slight.

There is a “you” referenced throughout “Protest Diary,” a writer who lovingly bakes bread and attends rallies with Cimafiejeva. That would be her husband, the Belarusian novelist Alhierd Bacharevic. The English translation of his most recent book, “Alindarka’s Children” (2014), was published in America this year, and has been described as a kind of “Children of Men” for linguists. It is the story of two children whose father is determined they speak only in their native language. They wind up in a camp inside a forest run by a mad doctor who “cures” children of their native tongues, allowing them to speak in what would be perfect, unaccented Russian. No rigid nationalist manifesto, the. novel ends on an ambiguous, searching note about the relationship between language and self-determination.

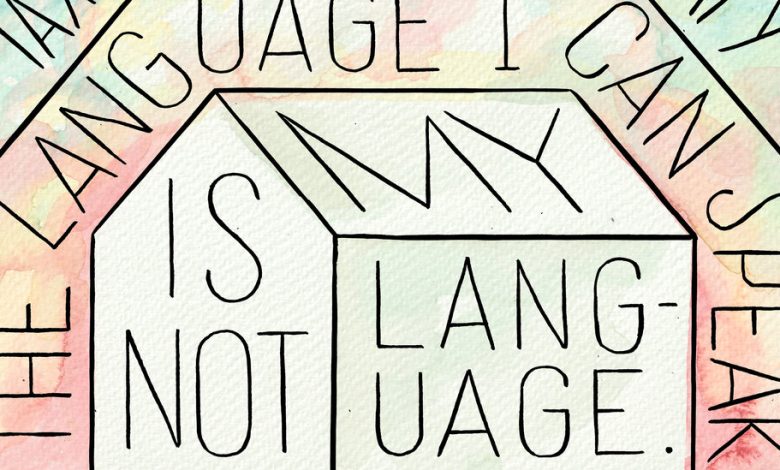

Similarly, in “Motherfield,” Cimafiejeva balances a commitment to Belarusian writing with a mistrust of nationalism. For her, that feeling is contained within a poet’s natural fascination with the imprecision of language. In “Negative Linguistic Capability,” she says her ideal language cannot be “contained in words.” She longs for an unruly language, political only in the sense of being ungovernable. “It’s a language,” she dreams, “for reading my own self/language for reading with mistakes,/because there is no one to correct me.”

As Putin has become bellicose in his efforts to keep Belarus and Ukraine within his sphere of influence, writing in either of these two national languages has come to be seen as an act of political defiance. Cimafiejeva, though firm in her convictions against the Lukashenko regime, comes across in these verses as less certain about language being treated so deterministically. That anyone or anything could be so easily defined seems to offend her poetic sensibility. In “Language Is a Prison Sentence,” she describes the burdens placed on language, the wounds it has been tasked with inflicting. “We want poems made/out of barbed wire,” she writes, “so that when we throw ourselves upon them in flight/we might feel alive.” She guiltily longs to escape this conundrum, “the prison of language,” so much so that she fantasizes about unintelligibility. She listens to freedom and sighs: “Its liberated hum/makes no sense.”

An insatiable desire to break free from the limits of a single national language is one of the hazards of Cimafiejeva’s other job. In addition to being a poet, she is a translator. Alongside her four books of poetry in Belarusian, she translates foreign poets (Walt Whitman, Stephen Crane) into the language as well.

Perfect then that “Motherfield” is a co-translation by poets from two different countries: Valzhyna Mort, who is from Belarus, and Hanif Abdurraqib, who hails from Ohio. Though the picture is even more complicated: Mort was born in Minsk, but has said she does not consider herself to have a mother tongue. At home, her parents spoke what she has described as “Belarusian Russian,” and her grandmothers spoke a blend of Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian and Polish. Belarusians describe this common linguistic mixture as trasianka, or “something shaken.” The term can carry a negative connotation, but poets, I notice, tend to find it exciting.

A dual-language publication, “Motherfield” reads like a testament to the innate multilingualism of Belarus. And after all, what Belarusians say matters just as much as what language they say it in. Plenty of the protesters who wound up in Belarusian jails — or worse — spoke Russian. The real legacy of speech in Belarus is that it has been unfree, in all languages, for far too long. In “The Stone of Fear,” Cimafiejeva writes about being handed down a “family heirloom” — namely, the fear of speaking openly. Imagining it as a stone stuck in the throat, she writes, “The stone will help you unlearn/how to say what needs to be said.” In “Motherfield,” Cimafiejeva has proved herself to be a bad student of fear. She wields her flexed, forceful verses like that mightiest of muscles — the tongue.

Jennifer Wilson is a contributing essayist at the Book Review.

MOTHERFIELD: Poems and Protest Diary | By Julia Cimafiejeva | Translated by Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib | 128 pp. | Deep Vellum | Paperback, $18.95